‘Most people will just look at the headlines of the Mail or the Sun, but not at the detail.’

‘Or where it comes from, and who is saying it.’

‘Ideas and opinions will get raised in conversations in pubs, not through the TV or reading. ‘How do you reach that, how do you influence it?

Smiles in exasperation. ‘I don’t know!’

– Baz, talking to me outside Tesco Extra, Dumfries.

I awake in a room at the Eglinton Hotel, given freely by Ray, its landlady, the previous night. Dalmellington has charmed me, and I’ve spent one of most pleasant evenings of this trip here, surrounded by warm and friendly company and glad to be out of the rain. Fatigue is kicked me over though. I’d stayed up late writing again, and end up sleeping well over my alarm. It’s time to check out, and I have to hurry out of the hotel. I pedal out, and manage to find a quiet cul-de-sac on the edge of the village where I catch my breath and watch the slow progress of the traffic out of the village. A man watches it too from a window, and we share for a moment in the most absurd of spectator sports.

The countryside leaving Dalmellington has been farmed with cattle, as has much of Ayrshire, and it gently slopes here and there with a pleasant though familiar aspect: green, farmed fields give way at their peaks to the beginnings of gentle mountains, marked with bursts of trees and shrubs. Further along, the road drills through a valley, small mountains sloping into the distance. It’s a relatively quiet road and there’s no threat of rain today. I pedal along gently, slowly building up a pace.

After some miles of plain old countryside polka-dotted with the marks of man, the road slides down into the small village of Carsphairn. A small heritage centre by the road grabs my eye, and I pull in to investigate. Inside a small hall is a social history exhibition of the women of the area.

A wander around the exhibits is well worth it, and each panel is carefully and lovingly researched. There’s tales of the women who would run the alehouses of the area, which often began as little more than open or public houses. Landlords would usually run the pub part-time, keeping up work as postmen, farmers or whatever paid. Women would keep households together and undertook a huge amount of domestic labour. Whilst the law accorded them very little status, testimonies give the impression of strong female figures that headed families and communities. The oral histories upon which the museum is based on, alongside photographs, give the impression of a warm and mutually supportive community.

Ruth tells me more about the exhibits. She’s a volunteer at the museum, and originally hails from Switzerland, but has lived around here for seven years. Over a map, she points to a plethora of intriguing locations surrounding the village. There’s Polmaddy, an abandoned mining village, its ruins sitting in the lap of the Galloway forest. Then there’s the remains of a mine itself at Woodhead. The Galloway Forest is now a tourist attraction, but as a park it’s relatively new, and there’s been a policy of planting forests where once was farmland. But the Galloway Hills abound in curious history, which Ruth shares.

After defeat to the English, Robert the Bruce hid from the English and rival Scottish factions in these forests, carrying out small raids, rebuilding strength, and eventually bringing together the forces that would bring victory at Bannockburn.

Or have you heard of the Covenanters? They were members of the Scottish Presbyterian Church during the 17th century who insisted on adhering to their practises of worship in disobedience to the orders of Charles II. They believed that every person was equal in the eyes of God, should be able to understand the Bible for themselves, and therefore had no need for Bishops or Priests. Theirs was a radical, democratic Christianity, at odds with the tyrannical belief in the divine right of kings. They were also largely ordinary people, and this part of Scotland was a major centre of their worship. Made illegal, they would secretly meet and worship in the forests and fields. Soldiers hunted them down, killing possibly hundreds simply for the brand of their beliefs, during the ‘Killing Time’ of 1684-5.

Just one more historical anecdote, if you’ll allow me. Some of the stones around Carsphairn village were seriously believed to have been thrown by the devil to destroy the local church during the 17th and 18th centuries. When a crow landed on the coffin at the funeral of one covenanter, the reverend felt it necessary to perform an exorcism. There’s one story of abysmally absurd local traditions which is worth sharing. After a Sunday meeting, worshippers leaving the church saw a figure struggling in the claggy waters of the river Deugh. They attempted to pull him out with a rope, but their efforts only succeeded in pulling them towards the water. The local minister appeared and ordered them to loose the rope, and the figure sank under the water. No body was found, and this was considered ample evidence that the minister had recognised that the drowning man was actually the devil. And so it goes.

As we talk, Ruth combs away at various straggly pieces of wool. Given by local sheep-owners, these can be repurposed and used for embroidery. The wool is thick and a little oily, and the black wool of Jacob sheep is especially soft and comfortable. She’s worried about Scottish independence, she tells me. ‘It will be so expensive, but they don’t realise!’ She raises the common concerns of the No campaign: what will happen with the currency, health system, or the border? Her concern is that the detail hasn’t been explained. But shouldn’t the Scots be allowed to work that out themselves, for themselves?

‘These sixteen year olds, they’ve been indoctrinated’, she worries, a little harshly. There’s been an unfair degree of prejudice against the intelligence of most sixteen year olds I’ve heard among older people. Yet when it comes to the detail, that which is most often sought, I find that the sixteen year olds trump all other age groups with their arguments, ideas and evidence. But there’s a strong element of age in the disposition of voters, I’ve found. The young and middle-aged are more likely to see the possibility of independence. They’re better able to realise that these problems are easily solved, and indeed, the Yes campaign have provided sufficient information as to what would happen with the NHS, or the border. These are non-issues, part of a general smog of disinformation and fear which has, I’m glad to say, not been that effective in Scotland. I do hope the Scottish vote in sufficient numbers for what’s in their best interests. As Ruth adds, ‘I don’t mind what happens, so long as we have an enlightened government’. Here here!

I take the road out of the small village of Carsphairn, and take a left off the main road onto a smaller rural trail. It’s a pretty and deserted journey that takes me first through forests and then out onto open ground. I cross the Water of Ken, and detour immediately left up an open hillside. It’s rocky and steep climbing and there’s no obvious path up to the top of what appears to be an ancient settlement, which makes the detour even more exciting.

Here an iron-age fort stands in ruins at the top of nearby Stroanfreggan Craig. Charcoal discovered nearby dates from around 7-8000 years ago, suggesting human activity in these quiet and peaceful hillside for an eternity. Ruth had given me directions here, and there’s evidence in the distance of other marks of human settlement. I take in the view, accompanied only by a small number of shy sheep, and wonder what the world seemed like to those men and women who stood in a similar spot thousands of years before, watching over these gentle lands.

Further up the road I pass the Southern Upland Way, but the road is generally a peaceful and easy pleasure. I past dry-stone walls, which to me seem like a natural wonder. Consider the effort and ingenuity in creating a wall that’s lasted for centuries, without grout, glue, or owt else? Forests at times take the place of fields and river, and eventually I reach the village of Moniaive.

It’s a large and pretty place, and after many miles of countryside appears like a beacon of light. I take a stop, and pedal up and down the handful of streets to get a sense of the place. These lanes are narrow and lined either with bungalows or small Victorian terraces, some coloured in a pretty spectrum of light pastel colours. I’m hungry, and after days of eating granola and dried fruit and nut, I decide a hot meal’s in order. The Craigdarroch arms sits at a crossroad and I head in. It’s a slightly chintzy but laid-back and friendly boozer. There’s an array of veggie meals, and I decide to treat myself to a veggie haggis, hoping it’ll be a little more substantial than the mush of Ben Nevis.

It’s fine and delicious stuff when it arrives, rich and filling, with delicious new potatoes, thing I’ve not eaten for so long. A hot meal! I think it’s the third or fourth time on this trip I’ve eaten alone in a pub or restaurant. I wash it down with cups of Goldihops and Summer Glow, and I am absolutely stuffed by the time I finish. Either it’s an excessively large meal, or I’ve been routinely under-eating. Either way, it’s superb fare, and a fitting tribute to my final times in Scotland. Tim’s the landlord, hailing from Fleetwood on the Lancashire coast. I ask him how he managed to find such an isolated and beautiful spot. He worked in Dumfries, the town I’m heading to, but chance played its part. He tells me a little about the place, before making suggestions about where I should stay tonight. ‘Don’t go to Annan, stay here!’ I’m told to aim for Powfoot, wherever that is. Onwards I head.

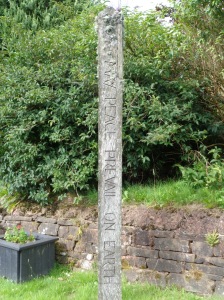

After Moniaive the road rejoins a larger A-road, and the journey becomes less interesting. It passes one or two pretty villages like that of Dunscore, with its blooming floral displays, pretty cottages and unusual wooden stile with its message of peace. There are the occasional ruined cottages I pass, shrubs From countryside it drifts into the vestiges of suburbia. The road becomes a dual carriage-way, and the drivers get over-excited by the additional space and speed up. There’s nothing to distract the imagination here, and the mind starts to become frustrated and bored with the grassy verges, high hedges and sprawl of litter. Dour semi-detached housing looms, and then the more familiar signs of a drive-thru McDonalds, a retail park, and a humongous supermarket loom ahead. Welcome to Dumfries, another British Town Centre, right?

I turn into the retail park and head towards the Tesco hypermarket, searching for dinner supplies. There’s the semblance of a community board in the corridor between outside and inside, a mixture of small ads and local community services. The supermarket itself is booming, and offers the usual bakery, butcher, grocery and fish-counter service that has annihilated inner town centres. Outside, I talk to a friendly cyclist unlocking his bike as I pack up.

Baz hails from the London area, but has lived in Dumfries for some time. ‘It’s a safe place, a safe place to bring up children’, he points out. The area’s quiet, and his children have been left to explore and play in the countryside around the rural village where he lives, something that just wouldn’t’ve been possible in the city. He enjoys the country life too, and cycles wherever he can. ‘When you have the internet, you can work anywhere. I have my own business. I can do that, and be here.’

But what is here? Is there anything to Dumfries? I’d asked people in the supermarket, and been given all kinds of suggestions. A cashier suggested a pub, a manager told me about some nearby castles, and a woman in another queue tells me about the museum’s famous camera obscura, and that the poet Rabbie Burns lived nearby. But today? ‘It’s mainly services, and farming’, Baz suggests, reiterating the sights on the road.

He jokes about the cyclists he often sees travelling through Ayrshire. ‘They have their heads down, they don’t look left or right. They just don’t see what’s around them.’ He’s part of the school of cycling slowly, of seeing what’s around you and being immersed in that. What need of a mileometer that someone will steal, or which will steal your mind’s interest into top speeds and personal bests? There’s more than enough here.

Dumfries itself is more promising than appearances suggest. It’s a small town which hasn’t lost its Victorian pretensions to majesty. There’s a small high street with chain stores, and a series of pubs around. An insignificant-looking station is surrounded by a string of relatively grand-looking hotels. I head into the Waverley Hotel, which is now a depopulated beer stacked with weird drinks offers, betting slips, and James Dean memorabilia. I sit at the bar with three middle-aged men, minds groggy with betting speculations and high levels of lager consumption.

A TV in the corner reports that today is the anniversary of the beginning of the First World War. Numerous talking heads rattle on about ‘sacrifice’, betraying the lived experience of soldiers who enlisted for a relatively short war, with their friends. What they ended up experiencing is one of the darkest and most brutal chapters of world history, and was to a large degree preventable. None offered their life in sacrifice – they were ordered in front of guns, into squalid trenches and exposed to shellfire. I fume in anger, and the fellers next to me steam in inebriation. One insists that the Racing News is put on. Each hands slips to the friendly young barman, who then calls a betting shop and places whatever bet they’ve chanced.

I leave Dumfries heading south, and join a quiet road marked as the ‘tourist route to Gretna’. It’s the early evening, my favourite time to cycle, and the sun is casting a warm light over the surrounding fields. The road passes a number of small villages as it heads towards the coast, including Powfoot, which turns out to be a small village with a surrounding beach, but I carry on, glad of the good weather.

The sun’s planning to set soon, so I head onto Annan, a small town up the road. It’s a bit shabbier than Dumfries, but retains in its reddy-brown Victorian architecture a certain pride in itself, even with its closed-up looking shops and pubs. I hear a brass band play in the distance, and one’s arrival into the town over a bridge is marked by a large flower bed with the lettering ‘lest we forget’. Outside a chip shop, a carehome worker tells me about the place, and her work. She’s obviously knackered after a long shift, but likes the quiet, laid-back nature of the place.

The road reaches Eastriggs, an unusually modern looking village. There’s a prim triangular green at the centre of the village, and a somewhat overwrought series of roads named after places of the British Empire spilling a little beyond. The style of housing is a kind of 1910s-20s red-brick suburbia, like what one would expect across the outer padding of any large English city. It’s a little incongruous here, but the mystery deepens when I pass a large building with the name of the Devil’s Porridge Museum.

An older lady is walking towards me as I gawp at this odd structure. I ask her what devil’s porridge is. ‘Hold on, you come here, I’ll just show you.’ And off we go.

The museum has very recently opened, and is open especially late to correspond with the WW1 anniversary. Devil’s porridge is in fact cordite, the explosive stuff within the bullets and bombs of the British Empire’s weaponry. It was Arthur Conan Doyle, writer of the Sherlock detective mysteries who coined the term:

‘There’s the nitroglycerine on the one side and the gun cotton on the other are kneaded together into a sort of devil’s porridge … this is where the danger comes in. The least generation of heat may cause an explosion. Those smiling khaki-clad girls who are smiling the stuff round in their hands would be blown to atoms in an instant if certain very small changes occurred.’

From 1915-16, the farms around Dornock and Gretna Green were bought up by the MOD, and within a year, a huge munitions factory stretched for nine miles along this coast, employing 30,000 workers. Sixty percent were under 19, and most were women. The villages of Gretna and Eastriggs were purpose-built to house these workers, and were designed by the pioneer of garden cities, Raymond Unwin.

Elizabeth takes me round the exhibits in a quick tour, as the museum’s about to close, but she patiently and helpfully answers my questions. I now know what devil’s porridge is!

There’s nowhere obvious to camp nearby, so I head onto Gretna just a few miles up the same road. It’s another model village of sorts, with a ‘Central Avenue’ and ‘Empire Lane’, and despite a plethora of shops, no real pubs whatsoever. The Irish navvies who worked in these factories were blamed for excessive drinking and factory managers shut down the opportunities for a drop not long after the factories opened.

Gretna’s become known as a place for young English people to get married. Just over the border, one can get married here under Scottish law at seventeen. The parade of shops reflects the popularity of this custom still, with a wedding dress shop, flowers, and a large registry office just opposite. I peer at the small ads in one newsagent window, trying to get a sense of the kinds of interests that people have living here. A woman stands nearby, and draws my attention to a WW1 commemoration event at the local church. She invites me to come. I do just that.

As I arrive at St. Andrew’s Church, a group of late-teenaged girls in munitions worker style costumes practice songs, and a man sets up a projector by the modern-built church tower, launching the image of a candle just beneath the steeple. He brings over another man with military connections when I ask about places I might camp. Some locals chip in with contrary suggestions and, finally, one of the Devil’s porridge volunteers who I’d talked to drives over and, from his window, suggests another location. All are near enough Gretna, but there’s now four places to scout. I’ll worry about it later, and join this friendly group of people into the Church.

It’s nearly 10pm, and there’s a group of mostly elderly people congregating around a table behind the pews where free cups of tea and biscuits are being served. ‘Is it always free?’, I ask, taken aback by the unconditional generosity. ‘Och yes, and every Sunday’. I mill about, but most people are settling into the pews. I spy a secret plug where I can charge up my camera’s battery, and join them.

For around half an hour, a group of seven girls sing popular songs from the war period. Whether it’s ‘Good bye-ee’, or ‘King and Country – we don’t want to lose you’, or ‘Pack up your troubles in your old tin bag and smile’, each is gaily sung with an eerie optimism. Each song suggests ignoring one’s doubts about the war, others put on a subtle but powerful pressure to join the army or fail in one’s masculinity. Others are just daft, and casually racist to our eyes, such as the singing ‘Paddy’ in ‘A Long Way to Tipperary’.

I’m not sure if it’s the intended effect, but I find the songs saddening, reminding me of the contradictory pressures on young serving soldiers, very few even remotely prepared for what they would experience, and most unable to forget it. The war was perhaps the worst catastrophe to British social life during the 20th century. All we have left is our songs and our clichés, lest we forget.

Two priests take turns to conduct the service, with one sharing some enigmatic and well-chosen words from Ecclesiastes 3.1-8, where the character God proclaims that he has made time, and compels everyone to relive time, over and over again, like a perpetual groundhog day. There are some hymns, prayers, and the service ends with the national anthem. It feels a little perverse to sing praise to the establishment which oversaw the drift into war and slaughter of millions without much consternation, but everyone joins in. Afterwards, we walk in a quiet procession to the outside of the church. We’ve been handed electronic candles. The community of us switch these on, and a piper plays. Another prayer is said and, at the turning of eleven o’ clock, we turn these off. A black-out to coincide with the time that war was declared in Britain.

It’s been somewhat moving, but the feeling’s ambivalent. I wait until the local community has filed away back to their homes, before taking a chance on a local sports field I’d been told about. It turns out to be tiny, little more than a space to walk one’s dog, but I find a corner that’s relatively quiet. Feeling worn out and blue, I pitch up my tent just by an electricity transformer.

Tonight there’s the most spectacular view of the stars. I can make out entire constellations, and trace the progress of satellites as they hover across this electric carnival of lights. Distant from such beauty by space, and time, reminds me of my distance from home, from a warm bed and the company of friends. The stars bring one close to the infinite distances that, in certain moods, one can feel from the lunacy and ludicrous tragicomedy of human life. With the gentle buzzing of electricity besides me, I gradually drift off asleep.