‘Money is still a big problem for us’ – Slavo, Margate.

My word, last night was probably the strangest experience of my life. As I awake, there’s nothing around me in the distance that would suggest red flashing signs or strange floating jackets or gently gliding samurai-like figures hovering over the shingle. Looking back, it’s actually a little terrifying, or certainly weird, the froth of a highly disordered brain. Like listening to Brian Eno’s ‘Lantern Marsh’ on repeat until one’s cerebral arteries collapsed. The sleep of reason… There’s something so eerie and empty about Dungeness. Wild-camping here sober would’ve been odd enough, but the added intoxicants seem to have momentarily torn through the veil of perception and hinted at a far more strange and inexplicable one.

The sound of feet padding through the shingle sends shivers down my spine. That night seemed to last forever, like a limbo without people or the possibilities of ever experiencing emotions again. It tapped into a taste for solitude and pointed out the isolating chaos at its core. In a bizarre way it reflects the myopia of seeking something that never actually existed except as a concept one already possessed. My eyesight impaired and my imagination running riot, I was compelled to wander all around this dark and empty beach in search of something that was already nearby me, that I should’ve seen because I’d placed it there. Does ‘Albion’ exist anywhere outside of a couple of poetry books and English literature surveys? My mind felt possessed in a way I imagine ants and other small insects are when the parasite cordyceps lodges itself inside their brains, forcing them to climb higher and higher so that its powerful urge can find a place to blossom and, in doing so, kill the ant. Some ideas can drive you mad.

Cycling is a male pursuit, and most I pass are middle-aged men who have spent good money on their cycle and equipment. We give each other a nod and carry on. The kind of customary loneliness of the long-distance cycler is difficult enough, but at least some normality’s retained in the B&Bs, restaurants and the like. Regular wild-camping, drinking and associated carrying on adds a series of wild-cards. The results have generally ranged from the spectacular to the strange, and have pushed me into challenging my own comfort zone and preconceived norms. But I don’t feel it has changed me in any way. And a weird night like that reminds me all the more, as if a thudding pain in the heart and head was not enough, or the unforgettably bitter taste of acetone nail polish remover in my mouth, that I need to get home soon and be with my partner, that ‘no man is an island’, of the truth of the essayist Francis Bacon’s remark that ‘whosoever is delighted in solitude, is either a wild beast or a god’. There are no gods here. Yesterday I talked about the possibility of accidentally stumbling across half-formed men on these marshes in the dead of night. Cut from what completes me, which is love, given form by my partner, I have stumbled upon the image of myself. I decide that for the foreseeable future I’ll stick with nothing stronger than three pints followed by a single good malt.

The beach is far smaller in the daylight, and already some fishermen have taken their places staring at the sea. Their multiple rods are held up with frames, small tents perched by the waterside, sufficiently capacious only to shield their balding pates from the rain. They seem to guard the shore from sea intruders like sentinels, with a severity and solemnity that is mildly terrifying. I pack up and leave, cycling up to the older lighthouse (Dungeness has two, confusingly, one being a little further inland than the other, though to call the terrain here ‘land’ feels misleading: it more resembles seabed, temporarily abandoned by the ocean, or more appropriately, a desert, with shingle instead of sand).

I cycle past the Pilot Inn, and approach a café besides the miniature Romney, Hythe and Dymchurch railway that terminates here. It’s a dinky thing that seems now like it was built only for passing tourists (‘world’s smallest public railway!’, once upon a time). Actually it meaningfully served the Cinque Ports and isolated fishing settlements along its root, like Dungeness, when it was just a murky settlement a little south of Lydd, without a power station. I realise that somewhere on that beach I’ve left my bike’s front light behind. I return, but cannot find it. Instead, I pop inside the railway kiosk seeking out more information about the place. I talk to a young woman from this area, who feels it has a very bad name. ‘People come here and say how barren it is!’ I share my affections for this place, truly like nowhere else I’ve ever been to, and she’s warmed by the words, and shares facts about the railways and the settlement here – there’s actually two nuclear power stations, and were once five lighthouses, and points me to the cottage of Derek Jarman.

I ride out with the power station behind me, facing Lydd. I pass a small group of birdwatchers and pass Prospect Cottage, home of Derek Jarman. Its garden is neither spectacular nor prepossessing, but possesses a gentle charm, an assortment of driftwood, ruins and unlikely shrubs all surviving, thriving, attests to the area’s unique quietness and remoteness, and to the possibility of survival in difficult, seeming unendurable circumstances. Indeed, for all the apparent bleakness of Dungeness, it actually thrives with living things. There are insects, moths and bumblebees that live here that cannot survive in any other part of the country. The area has more types of plant in its small space than anywhere else, over a third of Britain’s 600 varieties. The warm effluence from the nuclear power station actually attracts many seabirds, and all manner of unusual creatures surviving beneath the waste pipes. This is indeed, officially, Britain’s only desert, yet beneath the veneer of desolation is a landscape teeming with unusual life.

From Dungeness, I ride out to Lydd-on-Sea, an underwhelming stretch of bungalows that face an interminable beach. I still cannot find RX161, but I’m sure that it’s along here (and not Dungeness itself) that Time Bandits was filmed, a moment where a boy kidnapped by a group of time-travelling little men is stranded on a beach, between zones of space and time. One lifts a pebble here and throws it across the beach. It splinters the very air, cracking reality, revealing a more sinister and nightmarish world beneath.

St. George’s flags flutter over recycling boxes and parked hatchbacks and transit vans. They incongruously face the concrete sound mirrors and old Martello towers, structures seemingly built to repel invaders but which seem to express fantasies about what different forms of the future might look like. Different time-zones overlap here, sharing a same sound of seagull squawks and the moody breaths of the tides. Lydd-on-Sea merges into Greatstone, and I lose track of the different settlements, riding next into New Romney, once an old Cinque Port, now a small town with a large supermarket. I’m already feeling shattered, and decide to load up on sugars, gulping a cartoon of fruit smoothie followed by a pack of biscuits. Mental fatigue is crushing me. As I munch my food outside the supermarket, a Postman Pat kids ride continually replays its head-splittingly irritating theme tune.

I want to get home! This, above anything else, pushes me on through the small and tatty settlements I ride through, St. Mary’s Bay then Dymchurch, the English Channel to my right, and the Marsh to my left. Whole villages have disappeared on those marshes, consumed by malaria, plague, the elements, or rendered superfluous by the passage of time. Eastbridge, Fairfield, Snave, St. Mary on the Marsh, some with churches still remaining, others with nothing at all. I ride on through Hythe, another small town dominated by low-key residences, and push out towards Folkestone. Just the pebbles of the beach, and a modicum of housing. It’s Hythe I think where I wait a while besides a memorial bench, and it occurs to me how common it is to see these across these islands and nowhere else. To Joan, for Dad, in memory of Bill, ‘the light of my life’, ‘friend deeply missed’, ‘she loved this place’.

I reach Folkestone, a surprisingly interesting looking little town. I’d expected an ugly port, surrounded by disused edgelands sites – rusting sewage works, mothballed power stations, long derelict warehouses. Instead it seems to possess the decay of a seaside town, with great big Victorian housing blocks with jutting bay windows, offering in a rare quality of light that must exist on the right day. Today it is cold and overcast, the light icily harsh and grey. There’s a strange assortment of these massive housing blocks which, it would seem, seem now to house asylum seekers or refugees long-overdue a verdict from the Home Office. There’s a strange air about the town, one of obvious decline, though without any of the menace or misery so abundant in Newport. It even has a ‘creative quarter’ which, it is possible, may not even be such a bald-faced lie as most of these shyster property schemes.

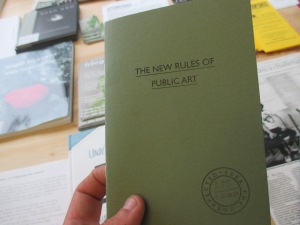

Its tatty and depopulated town centre has had some input from the adherents of Richard Florida. At the moment, the town’s art triennial is on, and the town has a number of art works around, from a large wooden house by the harbour to some pseudo-existential words stencilled on a lighthouse. I pop inside a pop-up shop displaying information about the triennial, with a few art works of its own. In one publication proclaiming itself ‘The New Rules of Public Art’, I read: ‘Artworks arrive through a series of accidents, failures and experiments’, its third rule. I’m at first inclined to scoff at this vague and faddish point, but I look around and see its argument in the town around me. Folkestone has suffered obvious decline, and what is taking place here is an experiment in what makes a town a pleasant place to be. The energies of artists imbue a care, attention and energy to a place, indeed they confer ‘place’ on what might be a ‘non-place’ (like the retail parks and bus stations) or just a ‘crap town’.

I expect that I’m biased towards my own interests, but I see more life brought and expressed by these arts events or a university campus, or a large and often-open public library, than any mall, retail park or huge supermarket. Their costs may be mocked, but they bring far more value to a place and constitute its community, and far less is spent on their establishment and implementation than any mega mall. As the same little book argues, community is created not from geography but out of common purpose. To quote Brian Eno, ‘sometimes the strongest single importance of a work of art is the celebration of some kind of temporary community’. The possibility of community always remains open, and interests me very much. What is it that makes Folkestone, for now at least, so much more lively, interesting and attractive than Hythe, Dymchurch or New Romney?

I cycle around the old harbour area, where locals eat chips and buy fresh fish from kiosk stalls still trading in the old Fish Market. From there it’s a tall order climbing out of the town, back through bungalowville and past a campsite optimistically pitching itself as ‘Little Switzerland’ (- well, on a bicycle some of these steep hills do feel Alpine…). It’s not long thereafter that I cycle into Dover.

‘A long habit of not thinking a thing wrong gives it the superficial appearance of being right.’ That’s Tom Paine, our man in Lewes, talking about Common Sense, or a lack thereof. One thing I’ve learned from teaching eighteen year olds is that our thought processes consist of loops, in which ideas, values, experiences lazily connect to one another by association. Our minds present with certainty ideas that often have a spurious though unexamined basis. These loops are unpicked by new kinds of questions, like those which young people ask in classes. Why is this the case, and not that? On a good day, one is divested of at least one prejudice. Common sense too is something ever transforming, whether we like it or not. Particular force comes from the young, those who so often constitute the front line of social movements and revolutions, though less rarely its leadership. ‘Time makes more converts than reason’, Paine adds. Will it be accepted in the future that five families in this country share more wealth than the poorest 20% of the population, around 13 million people? Or that last year alone, the average pay of FTSE 100 execs rose by 21%, whilst average worker pay rose by a mere 0.7%? Or that MPs earn six figure sums in other jobs that clearly undermine their ability to represent the interests of their citizens, and will gie themselves a 10% payrise, whilst nurses are denied any extra pay, and other public sectors only a maximum of 1%? I indicate pay in order to underline a general experience of diminishing living standards and increasing stress around money. I’ve seen poverty of a new kind all over these islands, a hidden poverty, one of arrears and debts. I wonder how this general experience of insecurity will shape the minds and expectations of young people in the future.

‘I have seen the future’ – back in Folkestone, I see these words on an image dated 10 November 1989 on the Brandenburg Gate. It is now around twenty-five years since that date. I wonder who could claim to have seen it now. It seems to have gone missing. Both the hope and the commitment to improving it is not to be found. Constitutional questions about the House of Lords or forms of voting are shelved. In spite of the extensive ugliness of late 20th century and early 21st century housing, retail arks and industrial estates which really do define a general experience of the British landscape, people in their cars will talk about football, television or heritage sites which to them hold more reality. The UK is still dreaming about its past, about its place in the world.

‘Its members were united in the way that tenants paying rent to the same landlord were united’, writes Julian Barnes in England, England. Yes, but in an early 2000s-built block of apartments with no obvious front door, its communal spaces and windows proportioned meanly under the imperative of cheap, where neighbours prefer not to acknowledge each other, uncomfortable with ‘weird’ common intimacy, complaining to their partners about the noises upstairs without ever doing anything about them. They feel disempowered, unable to do anything else. How can one see the future when one is dreaming about the past?

Can I see the future? No, course not, nor would I claim any one scenario more likely over the other. Ecological wipeout and an easy societal collapse then transition into green post-capitalism seem a little too remote and unlikely for me. I’m thinking, what if this present continues as the future, what if this retail park sprawl, this ‘suburbs of the soul’ as JG Ballard called it, gated, security-chipped, and insecure, is the general appearance and experience of the next thirty, nay fifty years? I see a retail park present extending as far forward and back in time as my imagination holds. The cheap food, free wifi, comfy chairs and extra chocolate chips all have that effect, mind-numbingly pleasing. They suggest that this is all there is, to the point that one loses track of one’s thinking, be it about the mind, or democracy, or a period of one’s life given over to experimentation or self-exploration. No no, those are whimsical, unproductive. The space for non-productivity shrinks whilst leisure becomes increasingly marshalled and pre-programmed: supermarket booze, widescreen TV, social media, Netfix.

Productive of what? It doesn’t matter. I think of social occasions before and my awkwardness in them, an awkwardness that now, looking back, seemed actually to be a general experience of most there, only I was too locked in myself to recognise that common awkwardness. The clumsiness of adolescence gives way to a brusqueness and cynical callousnessness in dealing with others. I’m a twitcher of the human species, and my life experiences and travels have given me an unusually wide and varied series of encounters. I find that arrogance and rudeness are most indicative of insecurity in adults, not something more obvious. It bothers me then that a certain arrogance is, if not tacitly encouraged, is certainly permitted in public culture. One becomes an island, self-barricaded with notifications about oneself. MPs and high-profile public figures are sometimes spotted Googling themselves at public events: this is a particularly toxic symptom. Invite your friends, have much to share, but then afterwards feel mildly disturbed by that physical proximity taking you out of the safety of a ‘tele-present’ world as Paul Virilio calls it, dreams on screens, desires about being an image of cool, intelligence, uniqueness, of interest.

Strange dreams. One actually feels happier this way, that’s the thing. No-one’s been duped into visiting the retail parks or not refusing the extra chocolate chips. Life feels much easier without the discomfort of people, and it reinforces itself like a cycle.

Perhaps the historians of the following century will look back on our era with a little more charity than I might right now. Perhaps they’ll write that collectively we were marshalled towards the least of all possible evils. By then, they may have given up on our Augustinian-Enlightenment fusion of a vision of the good, good alone, good triumphing through the right social and technological conditions. Perhaps, like the Gnostics and the Manicheans, as popular 2000 years ago as the heady stuff our much diluted C of E is based on today, they will scoff at the idea of evil being the absence or privation of good. They may think that evil is as present a force as good, that the two continually co-exist in a perennial state of conflict. Our striving, our demand for justice, peace, sustainability, transparency, they may applaud: useless striving, but striving all the same. The flesh is weak. Perhaps our actions or lack of won’t enable them to write any histories at all.

In this vast plateau of the present, I feel again like I’m lost on that shingle beach at midnight, extending each way to infinity. Everything is here, and opportunities are only conspicuous by their absence. One can feel powerfulness until another comes and brings a torch, a map, some food, who comes with the dawn, and then we all laugh together at our earlier feelings of confusions and helplessness. ‘I have seen the future’, histories looping, the desire of young people for a peaceful, fair and freer world. What could the future look like?

I’m not sure how any of this goes, but I feel it could begin with a burst of energy, most likely anger, attached to a refusal to be embarrassed by or to casually concede this feeling. Meaningful change is violent, undoing the habits and interests trapped in the past or invested in the present. There could be a corresponding shift to values normally derided by the ignorant materialism and social Darwinism of the moment, like slowness, like the soul, or care, or reason, or the future. It could understand itself not as a conversation, conference or theory, but as activity, as a set of actions that increases our collective power to act: defending public property and ownership, attacking surveillance, and so on.

Something should be said about why this quick call already feels hopelessly idealistic. I’m losing my conviction by the very word, the last sentence froze in blankness til I closed it arbitrarily with a ‘and so on’. It’s about the difficult in maintaining a standard of acceptable living. I mean living comfortably in a convenient, central and esteemed area, about being appointed in a job with apparent opportunities for self-progression, and about maintaining the set of actions and gestures that will maintain an acceptable life. Dress well, get laid, don’t eat excessively, have an ‘unusual’ hobby, work hard, don’t slack, sick off or steal. Don’t take drugs unless your friends are doing it, except if they’re mental health drugs, which no-one should talk about. ‘Ah, first world problems’, let the image of a destitution you’ve never personally witnessed marshal you back into a steady pattern of acceptable behaviours and mental loops. Increasing rent in high-employment areas, or decreasing jobs in low-rent areas enforce this contradiction. Living costs and rent/mortgages are perhaps the most potent form of societal control I can think of. One must work longer, and harder for it; even the disabled are now unexcepted. No police, or military, or glaring boss in a top hat, greatcoat and diamond-encrusted staff outside smoky factory gates.

Who can afford to take two weeks off work, never mind 122 days, to travel unproductively around one’s country? People often ask us about ‘the book’, the product or result that would make sense of render acceptable my actions. Because of my distance from it, and from you, I now recognise and am able to stress how powerful these imperatives are. A world where inherited wealth is king, the property ladder religion, and housing a kind of feudal vassalage. Again, domination isn’t in a military junta, nor even in the omnipresence of golden arches, supermarkets and chain pubs, it’s in our rents, it’s in the extra physical and emotional energy and adrenaline we need to keep our status, keep walking, always onwards and upwards, always doing, always busy, an exhausting mental and physical exertion.

Travelling along the Sussex and Kent coast, I’m reminded of Robert Tressell’s 1910 novel The Ragged-Trousered Philanthropists, dramatizing the exploitation of working-class tradesmen to make a wider argument for a socialist society. Tressell wrote the novel whilst working as a painter in Hastings, and the story’s set around the building of a house nicknamed the ‘cave’, an allegory of blindness and servitude lifted straight out of Plato. But Tressell’s perspective is jaded, and he argues as passionately against the ‘great money trick’ of capitalism and the wage relation, of corrupt local politicians and Christian hypocrites, as he depicts the ignorance and complicity of workers in reinforcing their own domination. As his protagonist explains to his fellow tradesmen how they’re exploited, he’s often jeered at and always misunderstood.

An uncomfortable degree of misanthropy is there, granted, but there’s a potent political point too. In one memorable example, Frank Owen gives the example of air. Capitalists have put a price on almost everything, including things which naturally belong to none. They would monopolise and sell us daylight and air, were it possible, and force everyone to work for it, or die. But Owen raises the uncomfortable point that most workers would happily go along with this, and willingly attack anyone who stepped out of line.

‘In exactly the same spirit as you now say: “It’s Their Land,” “It’s Their Water,” “It’s Their Coal,” “It’s Their Iron,” so you would say “It’s Their Air,” “These are their gasometers, and what right have the likes of us to expect them to allow us to breathe for nothing?” … And when you are all dragging out a miserable existence, gasping for breath or dying for want of air, if one of your number suggests smashing a hole in the side of one of the gasometers, you will all fall upon him in the name of law and order, and after doing your best to tear him limb from limb, you’ll drag him, covered with blood, in triumph to the nearest Police Station and deliver him up to “justice” in the hope of being given a few half-pounds of air for your trouble.”’

I have seen the future… the impossibility of conceiving change stems from education. The workers have had no education in politics, and their worldviews are an unthinking amalgamation of popular media and religion with an ugly deference to their well-meaning ‘betters’. Social aspiration only exists on an individual level. His fellow-workmen regard Owen as, at best, mad. This is all there is. They are the ragged trousered philanthropists because they give up their labour and its value in order to support a parasitic class of capitalists, church-men and politicians, and little object to it. They are lions led by donkeys, as Abe put it back in Inverness. They could withdraw their labour collectively and bring the country to a standstill, and force any government of the day to respond to their demands. But demands they do not have, and a feeling of collectivity does not exist. Instead, their begrudging complicity and unthinking endurance of the daily grind enables the existence of the relations that exploit them.

Speaking of dates, it’s now a century since the book was published. The working-class are not exactly starving or as generally malnourished as in Tressell’s time or as Orwell documents in The Road to Wigan Pier, but almost a million people were given emergency food by the Trussell Trust last year, a trebling on the previous year to that, and the marked increase in obesity and childhood obesity is linked, I think, to the proliferation of cheap junk foods. Orwell’s householders lived off ‘white bread and margarine, corned beef, sugared tea, and potatoes’ today it might be dried noodles, chicken wings, energy drinks, and toast. But my observations correlate with surveys of public opinion: there is a hostility towards an imaginary group of people either ‘scrounging’ or falsely claiming benefits, and a belief that such people, alongside immigrants and profligate public officials, are the cause of these years of austerity. A nice slip from the actual bankers who caused the economic crisis.

It comes back to education, or a lack thereof. One hundred years on, school-children are not educated about the politics or laws of this country. Change is still regarded as only possible at the ballot-box. Were a war veteran to stand for election on a platform of social house-building, full employment, opposition to global inequity, for balancing power between north and south, that person would be to the far left of Ed Miliband, yet I describe former Conservative leader Harold Macmillan. Parties today triangulate and share not only the same social background, but the same political commitments. There is no worth in looking to that, or to some intrinsic goodness within either. The ‘99%’ were politically outmanoeuvred again and again. Without a new constitutional programme, any left wing party that is elected in Europe will find itself in the uncomfortable position of overseeing increased taxes and interest rates as public infrastructure steadily declines, and will as quickly acquire the anger of the working class as they have their esteem.

Citizens are made, not born. Sometimes they have to be summoned into being. There were no ‘rights of man’ or ‘social contract’ to speak of until Tom Paine and Jean-Jacques Rousseau announced them as natural rights. Nature constituted a plane of possibilities. I’m inspired by something Marry Wollstonecraft writes. Surveying vast social inequality back in 1792, she wrote that ‘the neglected education of my fellow-creatures is the grand source of the misery I deplore, and that women, in particular, are rendered weak and wretched by a variety of concurring causes, originating from one hasty conclusion’. That stems from a belief that women are naturally incapable of reason, a view that was then reinforced by their consequent lack of education.

Would it be so bold to compare this position to that of the public today? Perhaps, but bear with me. Wollstonecraft occasionally compares the subordination of women to the disempowerment of citizens in politics more broadly. In her own time, there were little empirical grounds of demonstrating such an equality of reason – in her damning survey, women are at best educated to be delicate and swooning wives. Wollstonecraft’s point rather is theoretical: ‘it cannot be demonstrated that woman is essentially inferior to man because she has always been subjugated’. It took a vision of a future in which men and women were equals before reason, and an argument for this, which led to the ‘common sense’ of gender equality we now adhere to. Yet it would take 86 years before the first British university finally accepted female students on equal terms, and 136 years before all women were given the vote. Change is rarely instantaneous, and often it takes several generations before an insurgent opinion becomes the democratic doxa.

Like Tressell, I will not cheat the reader of my own suspicions, and admit that I cannot imagine any kind of progressive political transformation occurring on these islands within the next decade, with the exception, perhaps, of Scottish independence. [c]onservativism and cynicism are too deeply embedded here, and there are fewer opportunities for political discussion. People are too busy and distracted: whereas Owen could at least secure the attention of his fellow-workers during their tea-breaks, today agency workers would be barely granted time to piss. But small spaces of discussion and intervention do have an effect on keeping ideas alive. Even things like this public art festival in Folkestone, like the community centres and libraries I ride through, like the belief in ‘fair play’ which constitutes common sense in every pub across these islands. It is the young above all I have hope for. I hope they will see a future worth living for, one where they can live well.

I ride into Dover, the afternoon drawing to a close. It’s a surprisingly small town for one that seems to occupy such a large space in the nation’s psyche. Its white cliffs of chalk were often the first sight of travellers from Europe, and the last of those leaving Blighty behind, and their dramatic height imbues them with the symbolic power of a large fortification against the perils of Europe, the most prominent image of a ‘border’ for this one island nation. One can just about make out France from here. Given its cultural importance then, it’s surprising just how modest the town centre is. There is a large harbour and a row of creamy Victorian townhouses overlooking a promenade, and a remarkable castle looming above the town, but Dover is also characterised by ugly and functional apartment blocks, a grotty leisure centre and a lovelorn shopping area. It deserves more care than this. There should be some kind of welcome to the traveller, instead of confusing directions and an ill-thought town planning.

Still, it is a nice place and friendly. Two local women chat to me along the seafront and insist on the town’s virtues, handing me a map and encouraging me to stay a few days. There are plenty of curious looking shops, many for anglers, and some enticingly odd looking boozers. I ride around the town, where hair-salons, caffs and betting shops occupy spaces once known to Charles Dickens’ David Copperfield, Marconi, and more recently, Bill Bryson, whose travelogue begins with a series of disappointing encounters in Dover, resulting in him sleeping the night in one of its shelters. There is, unfortunately, still truth in his observation which begins with Dover and ends at Duncansby Head: ‘The trouble with English towns is that they are so indistinguishable from another. They all have a Boots and W.H. Smith and Marks & Spencer. You could be anywhere really.’

I’m keen to avoid history repeating, and with time disappearing, I cycle out by the Eastern Docks, still a very busy ferry port. I follow Route One, a rookie error. It leads up around ten staircases, high and steep, and I break myself in trying to pull and lift the cycle up each one. At the top of these white cliffs is a floral shrine to a late young man, and the trail threads round through a nature reserve with some fine views of the Channel. The path is uneven though, and my sleeping bag tumbles off here, and later some of the contents of my bike pannier, but the ride’s a pleasure. I cycle through pretty St Margaret on the Cliffe, then some more preened greenery, then through Walmer with its circular walls and towers, like a fungal bloom made of brickwork and Tudor paranoia.

Walmer merges with the ancient port of Deal, once one of the busiest ports in England, though now a harbour-village of twee nooks and crannies. Numerous lighthouses all round here attest to the dangers of the coastline for passing ships, particularly treacherous Goodwin Sands, and this stretch of the coast, with its proximity to France, has been the site of many wrecks and disasters. The Royal Navy’s barracks were targeted by the Provisional IRA back in September 1989, with eleven killed by a device exploding inside its school of music. They were band players, nothing more. The commandant-general of the Marines vowed to ‘end and destroy this foul and dark force of evil’, though the base’s security had been compromised by an inept private security firm charged with guarding the base, one of the first examples of the privatised outsourcing of state roles. The bandstand at Walmer Green seems so detached from its memorial purpose; perhaps it is just that those attacks seem so long ago, even though there was a time only two-three decades ago when the British prime minister was nearly killed by Irish republicans, and the City of London and centre of Manchester were heavily damaged by explosives.

Sandwich is just a hop from Deal, and is once again a pleasant and affluent settlement quite unlike the tattier and more obviously impoverished towns to its north and south. The first elephant and the first celery to arrive in this country both stemmed from this ancient, curious little town. I’d like to stop and find out more, but behind me the sun is setting, and I still have some miles ahead of me. Worse, the only route to Margate is along a busy main road. Without my bicycle light, I will be dangerously exposed. Slowness caused by fatigue has really set me back, and I do my best to push on.

This is definitely the hardest day of cycling so far. Saddle sores are becoming tender and painful, my knee remains swollen with its wound, and my mind feels like a madhouse of melancholy and morbid thoughts. Nothing else but to ride on, ride on. I pass by Sandwich Bay but the A-road is largely cut through an orderly landscape of petrol stations, dual carriageways and garden centres. I cycle hard towards Ramsgate but the distance is still considerable. Eventually I come close, retail parks suggesting proximity. I take the road towards Broadstairs and lose myself in a humongous shopping non-place, Westwood, a vast expanse of retail barns which must’ve wiped out all the trade in the surrounding towns. The car-parks are full. By the time I leave there it is around 7pm and fully dark, a real contrast to those glorious summer nights in the Highlands where darkness would set in around 11pm, and retail parks, drive-thru McDonalds and bland suburbia were as exotic as the bazaars, riads and kasbah of Marrakech.

It is now quite dark as I ride into Margate, a small seaside town with some obvious decline but with a fair bit of character under the surface. Outside the train station I meet Slavo, a friendly Slovakian artist and factory-worker who, with his partner Lucia, have kindly offered me a bed for the night. We cycle together back to their place in Margate’s old town.

It’s a little too dark to make much out about the town, so I’ll comment on it tomorrow, and instead we settle into their place. I have some food left in my bag – honey and fresh Kent tomatoes, and we make a meal of these with some bread, cheese and grapes, all served up with oolong tea. In the background, London arts station Resonance FM plays from a computer whilst they talk about their worries about global events. ‘Did you see the news? They’re about to start the Iraq war again…’ says Lucia. ‘This is an era where wars never end’, Slavo chips in. From Ukraine to the Ebola virus that has ravaged through Sierra Leone and Liberia during the latter half of my journey, stories that directly evoke fear and terror are broadcast on a daily basis. I’m glad to have been away from it. Such fear causes us to panic, sends us retreating into ourselves, seeking some kind of reassuring or safe image that might protect us, like an authoritarian government, against these distant, evil bogeymen and night-monsters.

They tell me about the hills and mountains of landlocked Slovakia, and Slavo recounts his adventures hitchhiking across Europe, and how one can survive for months alone in a woods. I’m often amazed by those who have travelled long distances, be it physically or mentally, yet it is remarkably common. They share their love of Scotland, particularly Edinburgh (‘just ten minutes and you’re in the mountains…’ ‘well, two hours!’), and are happy in Margate, where they’ve lived for around five years. Despite the low rents and Slavo working so many hours, they’re financially struggling, and ‘money is still a big problem for us’. I’ll talk more about the working poor and the precarious and difficult lives of some migrants tomorrow, as for now I’m truly worn out. I manage to keep it together long enough for a shave, wash and salving of wounds, before crashing out on their sofa. Two days to go.