‘Always go back to the source’ – Ariel, Horsham.

I awake in the cosy suburbs of Southampton. There are six days left now, sufficient time I doubt to ascertain the situation of these islands. Today I will push inland, off the coastal road, over the South Downs and into commuter belt territory. The South East, the ‘Home Counties’, lands of wealth and plenty, of twitchy curtains, casual hypocrisy and Daily Mail readers, those stiff-looking men and women in striped ties and floral blouses in the photos of Martin Carr, an area surrounded by as many clichés and ill-established assumptions as its mythic antithesis, the North. Let’s take a look at that.

My sleep’s been uneasy, and the fragments of some dreamt words lead to Percy Bysshe Shelley and the bees of England, a poem calling on the ‘Men of England’ to overthrow their exploitative overlords.

‘Men of England, wherefore plough

For the lords who lay ye low?

Wherefore weave with toil and care

The rich robes your tyrants wear?

Wherefore feed and clothe and save,

From the cradle to the grave,

Those ungrateful drones who would

Drain your sweat – nay, drink your blood?’

It’s the kind of thinking that used to stir me. Its rationale is happily simple: you already plough, weave and produce more than what would meet your needs, but this toil is stolen from ungrateful lords who leave you with little, a bare subsistence, an existence instead of a life worth living. Rise up then, England’s noble bees, and take what is rightfully yours.

‘Wherefore, Bees of England, forge

Many a weapon, chain, and scourge,

That these stingless drones may spoil

The forced produce of your toil?

Have ye leisure, comfort, calm,

Shelter, food, love’s gentle balm?

Or what is it ye buy so dear

With your pain and with your fear?’

Supermarket supply driver, carehome assistant, self-employed plumber, workfare scheme supervisor, secondary school teacher: wherefore plough? Shelley’s gambit cannot account for the choice to survive, that it’s preferable to live with a little than to go without, that there’s more pride and social validation in tolerating a straitened situation than in breaking the law or making a shameful show of one’s idleness. Few have the confidence of a large private income or the cultural kapow of an expensive education. There is far more pragmatism in the decision to abide, even if one’s obeisance reproduces that system. Few feel themselves exploited, except at occasional moments, historically over taxes, occasionally prices of food. When one feels like one has even a small stake in a system – a full-time job, a mortgage, a dependent family – then the cost of… anything else is too high. I first wrote ‘rebellion’, but what exactly does Shelley, or my younger idealistic self, the one who first left London 119 days ago, have in mind? Guerilla warfare, a peasants revolt? I’m not being entirely serious, but it leads to this problem, that many feel themselves to have a stake and to support institutions that ultimately disserve them, be it in frozen ways to pay for rising managerial salaries, or the ‘property ladder’, or much else.

I dress and pack up. Over breakfast, my aunt and uncle talk more of their experiences working in higher education, and their concerns about the future.

‘When you hear all that nonsense from the Daily Mail about how bad the current generation is, it’s all a load of nonsense. They’re a really good bunch, I love teaching the kids. … It may be a different way of doing things to how they did, but that doesn’t mean they’re not working harder.’

Good to hear! It’s become too familiar, this drubbing of the young. I ask Annie to expand on a point she made the previous evening about the efficacy of voting. ‘The poor don’t vote, and therefore are ignored in decisions’, she argues, and points to the Scottish independence vote. ‘Sometimes it’s important to concentrate on rallying as many people as possible to support the lesser evil. Getting people out to vote Labour rather than not vote at all would help stall some of the damage of the Conservatives’. Though the ultimate economic agenda of both parties has become similar, Labour would at least provide ‘more safeguards’ for the vulnerable, something that’s become apparent as these safeguards have been dismantled over the last four years. ‘The Conservatives’, by contrast, ‘are open about it, they don’t care’. Yet this sanctions what’s there. Isn’t not voting a more honest and thoughtful response to not having a possibility of participating or being heard?

That’s not enough, and not deep enough. It needs to begin with what we understand as ‘common sense’, our shared idea of reality and of ordinary behaviour, something shaped by our managed responses to material conditions. She invokes the work of Robert Cox, a theorist of international relations. In his framework, as I understand it, there are three factors involved in social change: ideas, institutions, and material forces. Attempting to instigate change through one alone is insufficient. Annie reflects on her research into NGOs and their failure to create social change. ‘They’re either co-opted or excluded’. The WWF is on many international boards, yet, as another researcher put it to Annie, ‘they mistake politeness for influence’. NGOs may be given stalls or take part in major meetings but this is little more than a formal acknowledgement of their work, acknowledging but ignoring. Annie spoke to one European commissioner about this.

‘‘How many applications do you receive from Friends of the Earth?’ ‘Kilos! ‘ he said in a strong French accent. ‘And what do you do with them?’ I just write a quick response and hand them to my secretary!’

Filed away and ignored. This effectively sanctions decisions made by those international bodies responsible for overseeing a kind of consensus of globalised capitalism (like the UN, the IMF, World Bank, WTO, or what Cox calls the ‘nebuleuse‘), whilst rarely affecting their content. Donations roll in, and occasionally even political leaders will sing the words put in front of them, but major international meetings have ended in indecision, and many developed countries later renege on their funding pledges. The opportunity to stall significant climate change has now passed, and historians of the following century will write harshly about the missed opportunity at the end of the 20th century.

Perhaps too much power is attributed to national governments, Annie raises? They are little more than ‘administrators for global capital’, and gives examples, from the Irish people being compelled to vote twice on the EU Lisbon Treaty in 2008-9, to bank bailouts. ‘That’s why people are not voting’. There’s a sense that these democracies are a sham not because of a decline in political parties themselves, who have increasingly converged into an amorphous gloop of chummy, plummy babble, but because governments no longer possess the sovereign power to manage their own economic affairs. Too much power is now ‘offshore’, in the hands of international bodies or financial players.

Worse looms, she thinks. Many banks and companies are now able to effectively blackmail countries into charging them ridiculously low tax rates or otherwise they will move elsewhere to another rival. The planned Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership agreement between the US and EU would make it possible for corporations to sue states whilst preventing governments from being able to protect their populations with regulations around fracking and the like. It looks likely to go ahead, continuing the long march of capital accumulation at the expense of ordinary people’s lives. Clearly that makes no common sense…

So tell me, ‘what is it ye buy so dear // With your pain and with your fear?’ Perhaps Shelley makes more sense when placed next to an even stranger contradiction. We talk about fear. After the success of the No vote in Scotland, I present a half-formed idea that fear is more operative in political decisions on a daily basis than desire, and that my initial Albion project was too optimistic. Fear always checks the desire for social change, from changes to taxation to education. ‘Who would pay for it?’ ‘The banks would leave’.

Annie relates this problem back to ‘common sense’, the way complex political and economic theories used by governments are then understood by the public, e.g. privatised utilities or wealth made in the financial services ‘trickling down’ to the millions of underemployed. Common sense needs to be changed, so that the demand for a universal free healthcare system that is entirely publicly-owned and run is ‘common sense’, that it ‘stands to right’. The NHS is common sense, and the free universal education of children from the age of five to sixteen is common sense. Pensions are common sense, as is the vote for women. Yet all were unthinkable in 1901. Common sense is buoyant – this is ours, give it back, we built this, this is our future – it doesn’t need a qualification to stand up for its rights, but it won’t apologise for letting reasonable thinking triumph other priorities. And in a time of continual defeat and fatalism, it’s needed.

‘I remember a couple of years ago, all my friends [many in education] were really depressed by the speed of these cuts. It’s an ideological project, one that doesn’t even work to a large degree, but the Conservatives are just continuing the project of Thatcher. And they’re doing it with such aggression and force.’ I’ve heard a range of testimonies now from different people in different roles in higher education that relate a common picture in higher education. Annie and Tony describe a confusing series of continual management restructures.

‘These management consultants were brought in and changed everything’, says Annie. ‘I remember one meeting, I was then the director of postgraduate research, and we were meeting to discuss the restructures. This woman [involved in the restructure] was there, and so was a management consultant. And I’d drawn up a detailed plan, because of a lot of things were inefficient. And this consultant sat there, as we were talking, and started drawing boxes. Different responsibilities by different people. And I said, that won’t work, things aren’t hard-edged like that.’ Tony’s plan was ignored.

Staff across the university had a lot of ‘informal knowledge’, Annie adds, but a suspicious attitude of new management towards staff meant that a restructure forced them to move into different departments where they had no background knowledge in the belief it would make them more ‘efficient’. Cue problems. Tony complains that administrators should be put on a course to ‘understand the purpose of the university, education and research’ but Annie points that many ‘can’t see beyond the edge of their nose’ because of the great pressures they’re placed under by managers, led by geometry-fond consultants paid by the day to produce vague yet ambitious plans that merit their huge fees. I wonder if there’s a pressure to perform on their part too. One vice-chancellor came in with a plan that involved attracting big-name academics, paid for by cutting most of the administrative staff. One ambitious staff-member volunteered to oversee the cuts. As staff were laid off, she would quote and use concept from “Lean Production”, a set of principles used in the automobile industry, maximising profit by reducing the human costs of the production line.

Angry workers tend to describe the specificities of their own situations at the expense of a broader picture of change across public life. What’s happening elsewhere? Look around, talk to people with relevant experience, pick up evidence, read broadly, before making a judgement. Annie suggests we take a second ride around Southampton to see another part of it, this time the old multicultural and working-class area of Shirley.

During the Second World War Southampton, like Plymouth, suffered major devastation from Luftwaffe attacks. This programme of demolition was continued after the war through the visions of town planners up until the late 1960s-early 70s. Shirley High Street became, for a time, the alternative town centre. Writers like George Monbiot, Owen Hatherley and Adrian Jones have condemned Southampton’s poor town planning, lack of civic coherence or ambition, and surrender to private corporate interests. Annie sees a city that has ignored its history and lost pride in itself, one of the few places where even Ikea could get away with building a huge store in its centre without a fight. On Shirley High Street, I wonder if a more upbeat and indicative possibility of civic identity might present itself?

Annie shows me the old façade of what she thinks was an indoor market. There are still a wide number of independent stores that continue in lesser form what was the ordinary shopping experience until the rise of indoor shopping centres during the 1970s onwards, of which Southampton has far too many – we saw this, way too much of this, yesterday. Annie reflects on the demise of street markets, particularly that in St. Mary’s, killed off by the dual carriageway and a series of shopping developments nearer the centre. Low-income communities have been cut off, ghettoised or split away across the cities I’ve passed through, from Leicester to Bristol. That said, the street market has declined across the country in most places, reduced to selling knock-off tat that the supermarkets and chain stores wouldn’t touch. Where they enjoy a modicum of health now is either in such tat stalls, often in covered indoor markets populated by pensioners, or as socially aspirational farmers’ markets selling overpriced condiments and vegetables. Neither caters for the average supermarket-led consumer, and so the street market cannot regain its former prominence as far as I can see.

The high street is still bustling today. Many Polish workers have settled here and started young families, though there’s less obvious sign of these new migrants than the talk in the town would suggest. It’s otherwise a familiar mixture of chain stores and local supermarkets alongside a refreshing number of local independent stores, from mobility centres to music shops, bookshops to Caribbean takeaways. It’s a good place. I’m told of its aspirational pretensions (‘upper Shirley’, but who will own up to what ‘upper’ connotes?), and Shirley Warrens, now where problem families have been consigned by exasperated housing officers. We pass Shirley Towers, where two local firefighters lost their lives putting out a major blaze, then head back to Annie’s, where I stop for a final loo break, before taking the road to Winchester. ‘Horsham’s very far, are you sure you don’t want to take the train half the way?’ ‘Oh no’, I smile. But it’s twelve noon, and I have seven hours to cycle around sixty-five miles. It’s a tough schedule.

Tonight I’m staying with an old teacher, and some deep-embedded fear of being late motivates me to pedal much more strenuously than on previous days. I ride north out of town, past Chandlers Ford, Otterbourne, a ten mile hike through retail parks, car forecourts and dull suburbia. ‘You twat’ is my greeting from a workman as I reach Winchester. At least let me open my mouth first! I’ve had abuse and aggression from motorists on at least a daily basis since Dorset. My manner of cycling hasn’t changed. What does it say about the South? Well, charitably put, they don’t like twats, wankers, bastards, arseholes, dickheads, fuckfaces, shitbags and other phrases I forget, particularly those on bicycles. We should celebrate their civic vigilance!

Winchester makes a fuss of its old medieval town centre and historical associations. For such a large town, it has admirably succeeded in keeping its old high street at its centre. Business and activity are thriving here, and other developers and planners in the country should take stock of what happens when one does not build retail parks and large malls on the immediate periphery of a place. I ride up to the Great Hall and the ruins of Winchester Castle at the top of the street. Surrounded by council offices and the remains of an old wall, the 13th century hall is large, airy and quite extraordinary. One can picture court gossip and politicking beneath these arches in the self-inhibited mumbling of the few tourists inside bouncing all about the walls, and great sumptuous banquets. Inside is a statue of Queen Victoria and a 13th century recreation of King Arthur’s round table, later painted by Henry VIII, a reminder of the power of those myths of honour, self-restraint and chivalric conduct among warriors even then. Was it also a manifestation of a cultural belief in human equality? It’d be tempting to read a modern value into another era, I’m unsure, but the symbol of a circle illustrates a form of power based on cooperation without hierarchy.

From the Great Hall, I descend down Winchester’s twee high street, past estate agents and upmarket clothing shops, towards its old market square. There are young folk singers entertaining locals sat on benches beneath the statues of kings. I’m enjoying the historical side of Winchester, but in truth there’s something naggingly dull and unpleasant about the place. I can’t quite finger it, but it first hit me when I arrived, and then when I began to see huge groups of student tourists wandering around. I felt: try Wells, Lichfield or York for a more authentic and interesting hit of ‘olde Englande’. The chain stores start to get wearisome. The city is obviously very comfortable with its own wealth, and the country’s first ‘public’ private school, Winchester College, still educates the children of the upper classes who board here.

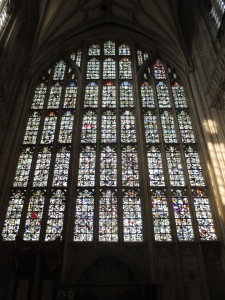

I continue, refusing to give up, and find the city’s humongous cathedral, a strikingly white Norman-Gothic fusion of mortal grandeur and divine submission. One must pay to enter, even if mere prayer’s your intention, and the cathedral’s pretty shameless about demanding more money once inside. Most visitors are here on a photo trophy hunt. It’s worth a look though, to peer up at the spectacular ceiling, which feels more distant than even the stars on a cloudless night, and to gaze at the intricacies of the stained glass, some centuries old. The cathedral’s prominence reflects Winchester’s own, once the capital of England under King Alfred and his descendants, a place where Vikings and then Normans lived and died, until its decline during the civil wars of the 12th century. There’s a prominent memorial to Jane Austen, who died and was buried in July 1817. She was relatively unknown as a writer in her lifetime, and only four people attended her funeral; only in the following years were her works discovered. Aside from Austen, the cathedral is much like any other gothic cathedral, though there’s some pleasure in spotting the 17th century graffiti, decapitated statues, and peeking around the small chantries, where the rich once paid for their own priest to pray in perpetuity for their souls. There’s a ‘holy hole’ too…

At the bottom end of Winchester’s high street is a prominent statue to King Alfred the Great, the 9th century leader of the West Saxons who managed to defend and then retake much of England against Viking attacks. Alfred established much of Winchester, and later rebuilt much of London. Though the one contemporaneous source about his life was a biography that Alfred himself commissioned (!), between its generous praise one gets the picture of a wise ruler who placed an unusual emphasis on education, and the rule of law. Alfred produced his own heavily Christian law code that stressed equality between rich and poor, and translated into old English numerous works of philosophy and history, like those of Boethius, Bede and Augustine. Though much of his achievements since are mythical and unlikely (founder of the jury system?), this wise and balanced ruler has been more inspirational to future rulers than any other monarch, except perhaps King Arthur. It’s a worthwhile place to leave Winchester, where history still steals the story.

I guzzle a large bag of dried fruit and cycle up into the South Downs. I’m pushing east, and I’ll be surrounded by these hills for another two days, great sloping expanses of grasses and corn, and beneath these, sloping chalk. There’s not much to the Downs, that’s got to be said, and I’m strangely a little disappointed as the miles pass and I’m no nearer those prehistoric wildernesses of Dartmoor or the Lochs around the Great Glen. I had secretly hoped to discover rugged majesty on London’s doorstep. Well, it is here, somewhere, and the place is still the playground of ramblers, those who are untroubled by a view that never seems to change. I prefer the speed of the bicycle. As children, my Dad took me and my brother here on our bikes, giving me the first taste of brutal hills and spartan youth hostels which I’d forgotten all about until this trip. The land is unusually fertile, and the farmers are relatively prosperous here out of the higher yields their lands give. The route is actually most pleasant straight after leaving Winchester, and there are some excellent views of the surrounding plains at Cheesefoot Head. Afterwards the route becomes mainly agricultural, and only changes its tune on approaching Petersfield, a very pleasant old market town.

I take a stop in its old square, where noisy school-kids chase each other and two market-stall holders commiserate besides overlooked bric a brac. The library doubles up as an information office, of which I receive plenty of inside. I talk to Kathryn, who then introduces me to David, an elderly local resident. He’s retired, and remembers cattle being chained up by the church to be weighed for market, ‘sheep everywhere!’ Neither are parsimonious in praise: ‘It’s a really good place to bring up children, it’s got everything you need, there’s good shops, plenty of things going on. It’s a nice place for children, and there’s a lot of arts, small dramatic groups. I’m part of the local crafts association. There’s so many activities.’ It’s easy to reach London but has that quaint market town sweetness that families seek as they establish new roots. I can see the attraction. But it’s very expensive too. Kathryn’s on minimum wage and her husband works in the Portsmouth docks, so they rent, whilst a career collecting tickets on the trains has ensured David’s provided for now. Both are happy, in all, bubbly and warm. As I wander around the rest of Petersfield, taking photos, getting water, looking around, that feeling’s reaffirmed by others.

Leaving Petersfield, the road becomes a little more busy with traffic, and settlements more contiguous with each other. Midhurst arrives soon after, another little market town though with less interesting features, then Petworth after, with its charming little square and medieval structures. There are some delightful market towns in the South-east, and I’m glad my overwhelming political pessimism about the place has left me a few surprise treats. The South-east is so prosperous compared to the rest of the country, and there is no obvious poverty at all, no foodbank collections, or Big Issue sellers, or even tatty looking motors, except for some extremely shabby Volvo estates with dog grills and animal charity stickers that, to my mind, attest to serious wealthownership. It requires a lot of money to be here. But these aren’t vacuous places, but steeped in rich history and nice to be in, filled with good pubs like those in Petersfield, an old coaching stop, or Petworth. I’m enjoying myself, but truth told, the familiarity of these places and the road-signs for London are reminding me of my wife and my cat, and of being home. It’s soon. The roads become clogged with stationary traffic by the time I reach Billingshurst, around 5pm. Horsham’s not far after.

The wealth of these commuter towns has me thinking about what a commuter is. One who doesn’t belong to the city they work in, here London, yet rarely belonging to the ‘dormitory town’ they sleep in either, instead choosing the place for its convenience. It reminds me of something I’d read by Danny Dorling about inequality and homeownership, in So you think you know about Britain? ‘The immigrants who have most disrupted stable communities in Britain have been the English themselves, buying retirement or holiday homes in places they like to visit, but where they choose not to belong.’ I think of North Wales, of the Highlands, of the experiences in Cornwall, Norfolk, even the Lakes. Decreased taxes, the sale of social housing and privatisation has allowed wealth locked into public property to be unleashed, allowing some individuals to profit. How can one person have enough for two houses, maybe even three, whilst many young can barely afford one? His or her hard work, they’ve earned it, right…?

Individualism wasn’t invented in 1979, we can look decades earlier in teenage fashions to understand individualism, self-reliance, a disdain of the tired ways of the old, Saturday Night and Sunday Morning etc. I feel it dishonest to say ‘collective spirit’s been lost’: I have no evidence of what ‘collective spirit’ was, cannot define it, and can’t even say any loss/rise in the last ten years. I think these kinds of vague categories are unhelpful and inhibit embracing the future. But the uneven distribution of resources is a problem. Not only for the present, for which most people alive now are begrudgingly compromised and unwilling to change. I mean for the future.

The further privatisation of schools/healthcare won’t benefit the lower middle-classes, or expand their ranks, as the actions of the Conservatives in the 80s. Massive companies are poised to profit. Tell Sid… tell him how G4S G4S, Serco, A4E, and Capita run his world, and why. It’s hard to see how many more young people can be pulled into the ranks of the professional middle-class if that is not already their social background. With less means of acquiring wealth, less opportunities for state/research council funded postgraduate education, wealth will more likely be transmitted by inheritance. The new rich buying second homes will pass these on to their children. Class divisions will increase, but their characteristics will change.

You can therefore appreciate the aversion across the genteel suburbs of this land to house-building programmes, like that in Longridge. Could we build a town here? Well, to be fair, there is some housebuilding happening in Horsham, but this is developer-led and little seems affordable. The brownfield wastelands and noxious swamps of the ‘Thames Gateway’ east of London, by contrast, are the proposed alternative, a place where truly no right-thinking person would choose to build a house or school. Any programme will inevitably reduce the value of properties in that area, which would be to reduce the wealth of its residents now, and for their future. What will they retire on? Uncertainty about the future of pensions, care for the elderly and retirement ages – all effects of the withdrawal of the state from providing cradle-to-grave social support, a withdrawal that is popular and has received a democratic mandate, lest it be said otherwise – is necessarily forcing people into reappraising their home as an economic asset. The private sale of council housing has given a far wider number of low-income workers a stake in this property system, the ‘property ladder’. It is worth bearing in mind that a policy to build new housing, particularly new social housing, would be unpopular in most regions it was proposed in, despite the obvious need for affordable social housing.

So for those still interested in social reform, I’d suggest thinking about these new changes. Wealth should be measured in the ownership of property, the modern ‘means of production’. Work, as in working-class, is low-skill, low-intensity, supermarkets, call-centres, distribution warehouses, barbers to beauty assistants, delivery drivers, less often, care-workers. Many workers belong to an agency, others are self-employed, so their means of withdrawing their labour is quite different. Automation has rendered many jobs superfluous to the minimal functioning of a town or city, and beyond paramedics, postal workers, police or public transport drivers, there are few workers who could feasibly cause a meaningful disturbance by going on strike. It would disadvantage them to do so. But what would make for an effective collective action? Rent strikes, debt strikes? Blockades and peaceful seizures of local authority buildings? I don’t know, it’s not for me to prescribe. But account for the last fifteen years before telling people that voting Labour, or Green, or joining that one-day picket outside the office is worth their motivation.

Wealth remains a major problem, and its inherited nature presents another obstacle. Most metropolitan commentators are probably unaware of its increasingly international dynamic too. Yes, let’s think about the situations of the communities left behind in places like Durham and the north-east, in some of the smaller towns of the Midlands, like in parts of south Wales or the south-west, and if it’s useful, talk about the white working class. I don’t think it’s a useful term and it doesn’t reflect how people in those areas view themselves, but it’s a starting point. But in most low-income urban areas in England, and one could apply this to Cardiff too, there’s a marked growth in families who’ve recently settled from across western and eastern Africa, from Latin America, from Poland and the Baltic states worst affected by recession, or displaced by conflicts in the Middle East. This has been a remarkable movement, particularly as entrance requirements have become very restrictive and needlessly prohibitive. The UK is a very hard country to gain the right to permanently live within, though as with much else, few of its citizens are aware of this and a contrary view is most commonly held.

This form of migration is more recent and more invisible: low-income areas are now to be found in the suburbs, not close to the inner city transport connections that the middle classes might use, and there have been no singularly forthright campaigns for recognition, no celebrity figures emerging from these communities. Christian and Islamic religious organisations are assisting these groups. When it comes to the practical relief of poverty and advice, religious organisations have been remarkably dynamic, and politically-committed socialist organisations have missed an opportunity to live up to their theory. There’s no common form of employment taken either, though there are shared characteristics that I indicated earlier: agency or self-employed, for instance, often insecure.

My point in making this sketch is to indicate that the young people growing up in these low-income areas will be necessarily excluded from the private inheritance of property, as well as facing the other social problems facing the young now, around low wages, unaffordable housing, and the difficulty of retirement. They are also excluded from the new popular messages of belonging and citizenship. They have ‘swamped’ these areas, they are told, a deluge that has sunk, rather than resuscitated, these crumbling suburbs. Their numbers must be cut; they do not hold ‘English’ values, which, presumably if one compares them to more favoured migrants, must be a love of buying expensive properties and sports cars. That no-one has integrated them into their cities or taught them how to speak English is their failing, not a social failure. That’s not to say that multicultural integration is itself a necessary pre-condition of a progressive society. Many second generation English overheard their white friends ridiculing the accents of people like their parents, indeed watched it as TV entertainment, before an eventual ‘acceptance’ was established, largely through football or takeaway food.

I anticipate that divisions of social class will increasingly take on an international character, partly as a consequence of discriminatory employment practices that favour (white) ‘English’ workers, partly out of a low-paying job market that only desperate migrants with few rights will be forced to take up, and partly as a consequence of this bank of private wealth commonly held, an ex-council flat, a small savings account, that will be transmitted through settled families. The ratcheting-up of anti-internationalist language will be an effect of this. Beneath concepts of ‘entitlement’ and ‘working for it’, unquestioned facts about social privilege and the inheritance of wealth remain.

Of course, not everyone is sitting on a ‘nest egg’ of inherited wealth: few possess something sufficient to buy a house of their own, though a large amount of young people will have been financially supported to varying degrees by their parents after moving out, be it directly, through a loan of money, or indirectly, as in moving back in with a parent (or not moving out) in order to save money. Though I received several scholarships and worked part-time in a bar, I wouldn’t’ve been able to have completed my masters degree without a seven grand bung from my dad. That said, my mum and my dad both own their own places in London, and so my stake in inherited wealth is high. Unlike many people, I will never need to experience financial destitution, and I will probably enjoy a very comfortable old age. But I grew up in straitened circumstances and through the state education system, and have chosen to live hand-to-mouth out of pride since moving out. The luxury of that choice, eh?

So with few actually benefiting from this class polarisation and this expansion of insecure working conditions, either xenophobic explanations will grow in popularity, or a frustration with politics may force a more intelligent and open-ended discussion about the future of England.

Let’s not forget that people still believe themselves to be equal, and believe that everyone deserves an equal opportunity to succeed, be it through work, study, sport, business, or whatever. This belief is coming into friction with the facts of inherited wealth. Though a lot of people would fail the history section of a citizenship exam, there is a shared belief in a democratic principle that I’ve heard in some kind of form all over the country. This is something also taught in our schools, to second and third generation English children. A belief that power belongs to the people, that political decisions should be made in the interests of the law-abiding majority, and that democracy is preferable to dictatorship. This belief is finding itself increasingly frustrated. The most interesting political momentum I’ve seen, and which this trip has reinforced, is this collapse of belief in the political process, strangely coupled to a growing interest in politics. If they really are all crooks, as is commonly thought, why follow the news at all?

A significant amount of the electorate choose not to vote, something that should be considered politically meaningful, a ‘none of the above’ vote that, were it counted, would be higher than the share that elects the average majority party in the Commons: as high as 40% in 2001, and around 35% in the last election. But a far greater amount of people do vote, though these votes are often made in a negative way, motivated more by keeping a candidate or party out of government, or choosing the lesser evil (‘Labour won’t be as bad as Tories’), than out of expressing a positive choice. This only makes sense in a first past the post system, where such compromises are necessary (‘I’d vote Green but they’d never get in’, ‘it’s either Lib Dem or Tory round here’).

The introduction of proportional representation voting, perhaps alongside a minimum salary for MPs, a publicly-provided budget for political advertising capped at a certain level, and the abolition of political parties, would together create such a transformation in the political establishment that much of this historically embedded frustration would disappear in a moment (of course, many new problems would take their place). What I mean is, this democratic principle and democratic interest is alive and growing. I see opportunity in it. A profound transformation is possible to the establishment of this country, and to these looming problems facing the young, but it doesn’t look like anything we’ve seen so far. The political commentariat won’t grasp it until it’s already happened, but I suspect that this desire for democracy will continue. What will come of it?

What will come of me… long and busy A-roads are remarkably some of the most conducive to speculative and imaginative thinking. My road ends at the edge of Horsham, a large town whose old market features have been a little obfuscated by the busy and thick roads that weave around it, but get by them (tricky, granted, on a bike) and there’s a really nice town centre. Much of it is pedestrianised, and from the old Carfax at its centre, a series of different lanes criss-cross at points together or traverse different directions whilst retaining a consistency of style and feeling. There’s a large array of mostly chain shops, but the town centre doesn’t feel either browbeaten by them or depressed by their abundance. A careful programme of investment that encouraged instead independent traders, clothiers and perhaps a large farmers market could be eminently successful. But I pedal around, interested by the town, drifting down the Causeway to spy 17th and 18th century houses, tumble-stacked against one another with the carelessness of a distracted librarian. The town is, to be fair, more dominated by the large offices of insurers RSA and a number of other corporate office blocks, but there’s something here.

I make a decision to explore it tomorrow, as for now, light is fading. I am due my rendezvous with Ariel, who taught me about early modern European philosophy and London’s literature during my History of Ideas degree at Goldsmiths, over six years ago now. I would sincerely thank him for encouraging and empowering me to pursue my own lines of thinking, permitted so long as they were backed with solid evidence. His confidence in my work led to have confidence in myself. Indirectly, my interest in Spinoza and democratic political theory owes him a great debt. Anyway, it’s been a few years since I last saw him, and so this evening is one I’ve been particularly looking forward to.

I find his house by the station and he welcomes me in. Over local beers, bread and ravioli, we catch up. Conversation threads over relevant terrain to this project. In particular, Ariel friendlily questions my research methods. ‘Who are you speaking to?’ My daytime encounters tend to exclude many people working, parents, and children, would only capture certain part of the population out of work, studying, and probably more likely to be disenfranchised. The form depends on the medium. The stories of young people and the ‘generational gap’ strike him, from my experiences, particularly around low pay and housing. Is the solution the restoration of the state to protect its people and produce the conditions of social equality? As I answer these questions, I find that my thinking is increasingly dependent on some kind of progressive and ambitious reform.

Conversations moves on to book-burning. ‘You know the old saying? Absence of evidence is not evidence of absence’. In his recent research, Ariel and a colleague have discovered that one particular historical source was misquoted accidentally to state book-burning. Countless major historians have since reproduced and written about this burning since without ever checking the source or is veracity. He laughs in disbelief, and it reminds me of the important of careful, evidence-based thinking. Nick Davies’ Flat Earth News made a similar kind of discovery about the modern press. Under pressure to churn out more news copy at a faster rate, journalists are increasingly reproducing stories from news-wires or PR companies without checking them for accuracy. Stories like the Y2k ‘Millennium Bug’ quickly ballooned from spurious outlets into major news, til the news itself became the news. Long investigative journalism is being abandoned in favour of urgency and production as news teams are cut down. Preference is for productivity without a timely and hence costly critical scrutiny. The Internet has played a dominant part in this transformation, and there are less safe spaces for ponderous, deliberative and careful reasoning, outside the judiciary and, to a decreasing degree, academic research.

‘Always go back to the original source’, reminds Ariel. Question and check everything, know something with certainty before making a certain claim about it. At a time when PhDs are hurrying out unoriginal research, and professors are churning out articles to meet the four outputs of the Research Exercise Framework on four different topics, it’s a timely reminder to keep one’s head and insist on producing sound, clear and original arguments, and to avoid clichés and popular fads. ‘My old supervisor used to describe it as like a black hole’: popular theories would draw in new research, and their proponents would seek out disciples to perpetuate their findings. Like a black hole, they might be unproven but they seem to fit in explaining things as they are, and it’s easier to think in terms of established modes. But one could instead be looking for evidence of new planets. Philosophy is ‘Talmudic’, quips Ariel, ‘commentaries written on the commentaries’, often little more than a new interpretation that accounts for the old interpretations. , ‘Are you going back to the original source? Are you looking in the archives in case there’s something new that hasn’t been discovered, or questioning the authenticity of something already there?’

There’s never been a greater need for critical, analytical thinking, but thinking back to Robert Cox’s model earlier, ideas alone aren’t enough: there’s institutions, and material forces, that those ideas need to relate to. So having spent the morning with two people either working or with long experience in higher education, conversation turns back to conditions with the British university system. Ariel discusses tuition fees. ‘Have education fees risen?’, he raises. Well, no…! It’s a counterintuitive point, but much of Ariel’s ethos is about questioning received wisdom. Their costs remain the same, whilst government funding actually remains pretty similar. They vary for subject areas, with humanities and arts degrees costing around £7k to £7½k per head, compared to sciences at around £21-22k per head. Science degrees remain subsidised by the state, research grants and third party investment. ‘Students used to think they were putting in three and a half, and then it increased’, but the cost always remained the same, only now that the ‘psychological burden’ changed. Students thought their education was becoming more expensive when fees rose to £9k. In fact the costs have lightly risen for humanities students, but this is an effect of ‘market psychology’, wherein almost all universities increased their fees to the maximum capped amount so that their degrees didn’t appear second-rate.

Are they paying more? The government provides the loan, repayment rates are low, and it may turn out to be unlikely that many students at all eventually earn enough over the course of working to repay the full amount and interest. Those who do repay the loan over a long period of time will be paying more, but this loan is unlike most others. There are no onerous repayments, no bailiffs, and evasion isn’t impossible. But Ariel draws attention to a more substantial change, to his mind, to the ‘psychological burden’ of the debt. ‘It tied the students into working’, into immediately seeking work in order to repay the debt, an unnecessary task in real terms, but in feeling necessary. A sixty grand debt… So the kind of critical or countercultural questions of the foundations of education or work, like that which appeared during the late Sixties and lasted around two decades, is no longer possible in the current environment, particularly when understood alongside the criminalisation of squatting, the end of the student maintenance grant, and the demise of the no longer-livable income once provided by benefits.

What about the endless corporate restructures and “lean production” in Southampton, and no doubt other institutions? Ariel is also concerned by a culture of management consultancy that ends up reproducing itself (solution: more consultants) and timetables for more restructures. The rapid increase in pay for university vice-chancellors seems to mirror the rocketing of executive pay in other sectors, whilst salaries and wages have either been restrictively capped or frozen. There’s a fear and a reluctance to blow the whistle in some settings, he’s heard. I share my own observations of bad practice in local support services, and describe what I’ve heard from within other parts of education and the NHS. We agree on a tough but sober reflection that whisteblowing of any kind will more often than not damage one’s own career without probably changing that workplace. Still, the example of Edward Snowden is a reminder that one has a duty towards the common good which must, at times, outstrip one’s own welfare. Difficult times.

Ariel’s been given a bottle of some superb quality slivovice, which helps wash down the Italian telera bread we keep scoffing. He’s brought it back from Italy, where he’s been living with his wife and son whilst she completes a research project. Teaching brings him back to London, and the geographic separation of partners for purposes of work is an unfortunate but common feature of such work. He shows me a collection of fridge magnets acquired from countless holidays across Europe, an exhibition of his family’s love of travelling. He moved here with his partner and son ten years ago from Camden, seeking in Horsham an area that had more space and was safer whilst still being multicultural and welcoming. Like my partner, Ariel came from a working-class household but was able to complete his school education at a fee-paying grammar school thanks to a local authority scholarship. Funding for these kinds of scholarships were cut by the last Labour government under the rubric of increasing social mobility, but they have had the opposite effect, closing entrance to the more academically gifted (and heavily encouraged) children from lower-income households. (That’s not to say that there aren’t already many more difficulties afterwards, like the difficulties of culturally fitting in at such schools when one’s parent(s) don’t have the money for private music lessons, horse-riding, nor live in a mansion…)

‘It’s like we’re moving back to the 1930s and 40s’, ruled by a small elite that really does know each other. Ariel was at Oxford during the heyday of the ‘Bullingdon Club’ when George Osborne was in the year below. Back then, a maintenance grant gave enough for a basic living, but the costumes necessary to participate in the club cost over £1500, well more than the grant and so demonstrating already sufficient familial wealth in being able to buy and wear it. Ariel tells another story of a friend with an important role in a prestigious girls secondary school, which often receives visits from business leaders and MPs who will give talks, and offer to take groups around parliament. Their mothers are already socially preparing them for marriage, and for specific professional careers. The fees are, of course, very high. It may be a strange admission, but I have full sympathy for rich people wanting to avoid paying taxes or sending their children to the most elite private schools. They’re acting in their own interests, which is what I’d expect of any social group. There must be safeguards and checks to ensure that every child living in the country has an equal social opportunity, and this is not the case, has never been the case sure, but is worsening by the year.

What does all this mean, ultimately, for the bees of England? Ariel suggests a crisis of the ‘champagne model’, and paraphrases the historian Lawrence Stone. He argued, as I understand it, that the reason why England had no major social revolution after the Civil War compared to mainland Europe was because the most ambitious and able members of the lower orders were allowed to slowly rise to the top and come into positions of power. The best were co-opted, the rest stalled. The outlet now? I’m confused, deeply confused, by all of it. Time for some new common sense.