‘I’ve never done this before’, says a female pensioner, ‘but I’m sitting out here watching the world go by. And there’s a lot of young people here…’

‘And they’ve all got mobile phones glued to their ears!’

– street talk outside the Swan Walk shopping centre, Horsham.

I awake at my old teacher Ariel’s house in Horsham, surrounded by collections of William Blake’s prophetic writings and intricate pen-drawn maps of mysterious scenes produced by his son. ‘If it were not for the Poetic or Prophetic Character, the Philosophic & Experimental would soon be at the ration of all things & stand still, unable to do other than repeat the same dull round over again’, I read in Blake. ‘Warning, this is a teenager’s room’, announces a sign next to that. I hope he doesn’t mind.

The wound on my knee is now definitely infected and has become painful to move. As I pack my belongings away, the lettering from my replacement pannier peels off in my hands, the Altura brand logo reduced to ‘RA’, whilst a sizeable hole has appeared in the other bag as its stitching unravels. Even the saddle is torn, spilling out foam. I’m wondering who’ll collapse first, me or this faithful bicycle.

We’re both up early, and Ariel has a busy day at the university. Over breakfast of coffee and cereal, he discusses the necessity of mobility in academia, ‘you’ve got to prepare yourself to move for work’, and talks of colleagues commuting by train or plane from international cities, rarely seeing their partners. It’s a profession that demands more than merely good work.

It is a ‘way of life’, in a not dissimilar way that farming or fishing are ‘ways of life’, a form of work that require a level of intensive personal commitment in order to succeed. It is also defined by a high level of competition and rivalry. There has been no sustained opposition to the ‘marketisation’ of the university as Andrew McGettigan calls it, except among some students who have protested and occupied parts of their colleges. I’ll explore one of these later today at the University of Sussex, Falmer. Instead the latest form of auditing, the REF, which every academic I’ve met so far has talked with either frustration or cynicism about, is one that has been if not embraced, then certainly accepted by academics, perhaps providing a platform to express competitive drives for success. Who wants their research, in essence themselves, viewed as second rate?

This is creating a hierarchy in the universities between quality research and grants awards, and the more lowly business of teaching students. The latter is being increasingly sub-contracted to PhD students on scholarships, and junior academics on short-term contracts. I cannot help wondering if the rapid recruitment of PhD students by universities on such scholarships over the last three years is a device to provide cheap teaching whilst academic staff produce the research and grant applications that give the university its reputation, then attracting further students, and further chance of success with grants. There is certainly very little opening opportunities for lecturers or post-docs after PhD, and many will find themselves unable to find a job after. Unusually exemplary research and patronage will make the difference. I’ll find out more about this later when I meet my friend in Brighton.

We talk about something which had hogged conversations yesterday, about the rise of a managerial class and their dependence on expensive consultants, which have restructured the basic operations of workplaces in ways that they didn’t begin to understand. If anything, their shape-drawing, arrow-pointing ‘thinking out the box’ zaniness eschews competence and experience, with consequent confusion, disorder and irresponsibility across administrative departments. Strangely, salaries and wages have been frozen for teaching and support staff but rapidly increased for managers. ‘Chancelling’ has become the new word for a kind of expensive and inactive incompetence not seen since the abolition of hereditary posts in the armed forces. But this problem has heavily blighted local government departments for around a decade, with many restructured regularly with cuts to staff to the stage where in the end they become inoperable. This aided the arguments of free market fundamentalists, behind these efficiency restructures with their ‘lean production’ bibles, for then privately tendering out services to private companies who claimed they could run those services more ‘effectively’. Since then, a decade of frozen salaries, data losses, bungled IT systems and, in many social service departments, catastrophic cases of oversight.

It’s a mistake, I think, to appeal to reason here, to approach some hydra called ‘neoliberalism’ with a series of arguments about why privatisation is bad. Bad for what, or for who?, is a more incisive question. It has been good for individuals with private stakes or connections with outsourcing firms, good for wealthy individuals with assets and shares in companies involved in these, including major accountancy firms overseeing tenders, or with savings in banks investing in these. The problem begins when individuals are able to pursue their commonly-held desires for self-enrichment without effective safeguards and restrictions against these desires harming the rest of society. The solution begins, I think, at a constitutional level. But when the unwritten constitution has itself become dispersed into the control of diverse private operators, making an appeal to reason or common sense alone changes nothing.

For the most part, Ariel shares practical and helpful advice with succeeding in academia, and the value of approaching a problem historically. ‘I’m glad all that training wasn’t quite wasted!’ I’m given suggestions to explore different parts of Horsham, and we walk up New Street, built in the 1890s, with some attractive and well-designed local authority housing built only in the last two years, easily fitting with the street, desirable-looking homes. Horsham a large commuter town, larger than it would seem (its population around 60 000), in the shape of the figure eight from east to west. I wander through the attractive park and its gardens, people walking their dogs.

I talk to one lady who describes herself as from the north, but by accent what I’d place as probably the Midlands. She talks about coming from Peterborough to move here, ‘I love it, it’s lovely’, but why? Well, like other nearby towns, there’s a good deal to do: activities for the young, schools and colleges ideal for bringing up children, relatively affordable good housing, a good shopping centre, and community activities of a general kind. She finds it much better than where she’s lived before. As she talks, she admits feeling ‘overrun’ with the social changes to the areas of the north. She complains about a mass migration of Polish workers, ‘you don’t hear English being spoken, you feel like you don’t know where you are’.

This sense of cognitive dislocation isn’t that commonly reported to me but it would seem to be felt by many people, and the problems it presents I discussed in detail back in Lyme Regis. As I argued whilst travelling through the Midlands, anti-Polish rants permit a soft racism that doesn’t see itself as such based on the same colour skin as the white English or Scottish people expressing these opinions. But these opinions are so often discounted, and in doing so deny this feeling of dislocation and abandonment that people mainly from former ‘working class’ (as a self-aware, mainly industrially employed grouping) describe. There has been a massive amount of immigration to smaller towns without any real debate or agreement from people living in these places already. This can be seen to a lesser extent with the Home Office’s dispersal of refugees in stranded council estates in deprived towns. There are few support services on the ground and no service, that I’ve found at least, and I’ve looked, which seeks to bridge divides and link new migrants with individuals and communities into the places they move.

Instead they begin to establish their own communal facilities, the Polski sklep, the street-corner where men or families will sit out late talking, and which seems like ‘over-running’ the traditional social mores of the settled neighbourhood. Feeling ‘overrun’, they might seek to move elsewhere, though I find from observation that areas with higher degrees of support for racist or anti-immigration political positions tend to be homogeneously white but close to areas which are not – proximity, rather than contact. Perhaps they’ll associate migration with crime, but more often it’s a feeling of anxiety about their own identity, and their own importance, being neglected and subsumed by this larger and sometimes more economically active group. And we don’t talk about it in this country, except in the language of anti-European xenophobia, which whilst releasing some of the pressure still doesn’t actually face the issue and dissatisfaction with non-white immigration by parts of the white English or Scottish population. Racism is appalling, and stems from ignorance, but to believe that the problem lies only in the attitudes of settled communities is to greatly disserve their own needs around identity and community. It can feel anxiety-provoking. I suspect, but hope not, that my comments will be seen by some desirous to take offence on behalf of others as a kind of insidious racism. If the opinions and feelings of a sizeable group of white working-class people continue to be dismissed, particularly by those on the Left, there can be no hope of popular political engagement in turn from them.

The Left’s melancholia remains a mystery to itself (I’m thinking of the recent writings of Paolo Virno, Franco ‘Bifo’ Berardi and Mark Fisher), but to my mind can be explained by the realisation that ‘historical materialism’ has failed. Capitalism will not inevitably collapse and lead to Communism. Communism has been partially realised in state form and been proven, largely, to be even more authoritarian than what it replaced, though effective at industrialising rural economies through centralised government. But the rise of capitalist China particularly indicates that collapse is not inevitable, and rather that international capitalism is going to continue in its ravaging of the environment and of human lives in order to return a surplus to a tiny and unaccountable elite. From state Communism in Russia, China, Cuba or elsewhere, to the inaction of many trade unions and their self-serving leaders, to the lasting failure of Eurocommunism and social democracy to enact a never-realised vision and standard of political organisation, the Left finds itself disserved by societies, histories and humans as they are. Rather than reappraising that vision, there is a deadlock of melancholia, or a tired rehash of the old ideas, or even, just as absurdly, a kind of monastic refusal of the state or ‘power’ altogether, in favour of a dispersed multitude or grassroots networks that have either never existed or been outmanoeuvred everywhere by more decisive political actors, from Athens or Cairo to Kiev. What’s been most interesting about new Left political actors like Podemos in Spain is their refusal of conventional politics, their refusal to talk or play politics. They begin and end with the people, through transparency, and through means of direct democracy, even remote. And that Podemos don’t see themselves as ‘Left’, or ‘Centre’, or ‘Right’, or anything, except acting for the people.

To what service then is critique and critical theory, other than to locate the social or environmental problems produced as a result of it? Such research is most fruitfully done within a research institution, and many left-wing activists have entered universities as PhD researchers, like me, hoping tendentially to secure a career in the universities but then curiously just as critical of the universities as any other institution, if not more so. But in doing so it removes many potential social reformers from regular communication with disaffected working and unemployed people, many without degrees or a traditional interest or knowledge of politics. The value of our research is to reinforce some popular theory or thinker in our fields, reinforcing a paradigm as the rest of the society around us drifts to more unchartered, uncertain and swampy political territory. I understand this, and I see the hopes and problems of my own position far more clearly now in my distance, as I write these words not in a university library or on a desk crammed with early modern European philosophical books and notes, but outside a chain coffee shop opposite the entrance to Swan Walk, among the stay-at-home mums, pensioners and students of the town milling by, drinking my chain-store espresso coffee which tastes the same here as it does everywhere else, reassuringly so.

Well, getting back to our conversation in Horsham Park. I give the example of Irish immigrants to the major cities from the mid-19th century on following the potato famine. Contemporary accounts describe the extremely deprived slums or ‘rookeries’ with a distinctly Irish but to their minds what we’d call ‘ethnic’ character. The Irish stood out by their Catholic religion, until recently persecuted in England and Scotland, as well as for their different accents, social mores and even appearance. ‘We wouldn’t say we’re overrun with Irish migrants now, there’s been a process of settling and integration. Could the same happen with Poles?’ She’s unsure, but complains that nearby Crawley is overrun. The conversation isn’t wholly negative, and we’re largely talking about life in Horsham, but these problems stand out most, and I share them here, unsure of my position in response. I think of complaints by white working-class Londoners in the inner London communities I’ve worked in (to a small degree), and those who have moved to outer London suburbs or surrounding counties (heard to a much larger degree), and they are similar in nature. And I feel sympathetic to their feelings of communal loss and alienation, though disagree that migrating workers are to blame. A larger and more volatile question about the role of the state in receiving migrants, in social housing, and in the problem of low pay, remain.

I wander back through Horsham town centre, past a ten-pin bowling centre and along its shopping streets. There’s a number of interesting historical plaques embedded on the floor of the bustling East Street. Where in the UK was hit with the heaviest recorded hailstone back in 1958, a hefty 140g ice bullet? Alfred Shrubb was one of Britain’s most successful runners, breaking seven records in 1904, but where did he run a tobacco shop? Perhaps a smoke truly was good for your health, as the old ads attest. The town has a large museum with free entry, and it well rewards a few hours’ curious exploration, with exhibits that cover Horsham’s history from paleolithic times to the construction of the RSA building and the Tesco out of town retail park. I’m not sure which I find more gruesome, the tales of acid bath murderers, husband-strangling, executions by being ‘crushed to death’, or the terrifying cyborg mannequin the museum keeps in a small cell, its arm oscillating up and down with a loud and creepy slowness, expressing not so much the sufferings of 19th century prisoners, as the terrifying ghouls and spectres which haunted their guilty imaginations…

A local painter wanders up and approaches me, interested in the movements and thoughts of visitors here. Her name is Becky, and we talk for some time about crime and punishment besides the weird robot. She lives in nearby Southwater, and worked as a nurse until health problems pushed her into early retirement. She’s just finished a fine art degree, and is fascinated by the stories of people. A perfect conversational partner! I love artists and wish I could paint with some degree of competence, to properly render the sights, characters and experiences I’ve encountered and which are etched inside my mind, but all I have is my words and I try my best with those. She asks why I’m at the museum, and in describing my journey, I tell her about Horsham and the south-east, and the ‘fear of crime’ I’m coming across, particularly in affluent areas. Is it because those people have more to lose, or a reflection on the domination of fear and terror in newspaper headlines?

Perhaps it is a mixture of the two, she replies. Even if people are sceptical of what they read and hear, these headlines are remembered and internalised (as conversation reveals) and there is a feature of human nature to more rapidly recall negative experiences over positive. Becky worries about this, and ties it to a decline in ‘society’ as it is felt and lived as a practice of communal activities. She worries about people being attached to screens, never looking up, and I think of the children kept quiet or ‘educated’ with games on tablets. There would seem to have been a decline in group game-playing, say in parks and streets, in the last twenty years, though I’m probably too young to make this comparison with much evidence, but it’s something I feel. Perhaps people older than me can take a look around and tell me if I’m wrong.

She worries that it will lead to an irreversible decline to live and take part in communities. ‘There’ll be nothing left’, and it reminds me of the under-reported problem of isolation and loneliness among the elderly. Loneliness on the whole would seem to be a real social problem. We get back to the activities of young people, and she tells me about her children. ‘When I was young, me and my three younger brothers would take a picnic and go down to the river by the day. My youngest brother was two. And my parents were at work, and would leave us to it.’ I forget to ask whether she’d allow the same for her children, but the point is that such a thing would be unthinkable and probably considered dangerously negligent. Children are surrounded by fears of the outside (strangers) and in the inside-outside (the Internet), and parents feel bound to obsessively protect them. Anxieties are communicated this way and passed down. What to do? It’s not as black-and-white as all that, but there seems to be some kind of social shift occurring. She found Southwater very empty and lonely after she stopped working. In Horsham, it seems, there’s a little more to do, but it reminds me of a consistent problem I’m encountered: what is a town supposed to do? What is it not doing?

I love the ethnographic collections here, particularly the prayer flags and Buddha statue. Out of all my studies of major religious scriptures, I’ve been impressed by Buddhism: its ethical instruction does not depend on supernatural phenomena or terrifying images, and is based on substantive reflection on common experiences of suffering, ageing and death. We humans generally cannot bear to recognise a meaninglessness to our lives. Even the biological materialism beneath modern atheism supposes a scientifically-graspable, universal order beneath human lives (‘we’re made up of atoms, we return to matter, we all die…’). The Buddha’s ethics rest on an incisive psychological argument: we experience life through our thoughts, emotions and desires. ‘Our life is the creation of our mind’, he writes in The Dhammapada. If one uses reflection to detach these thoughts and desires from their external events, they can be understood not just as inevitable consequences or effects of those events, but also causes of those events. An uncontrolled lust for an object (or objectified person), an uncontrolled desire for some status or achievement, an uncontrolled emotion like anger or hate against someone you judge to have wronged you cannot be completed or resolved by their expression. These drives aren’t based on a lack to be fulfilled; they’re endless, and rage and rage until one has become able to master them.

‘There is no fire like lust, and no chains like those of hate. There is no net like illusion, and no rushing torrent like desire.’

The Buddha’s suggestion is a self-withdrawal from a life and a devaluation of existence, no more than a ‘bubble of froth’, ringed all round by endless suffering and death. His followers recorded his prescriptions in a specifically mnemonic manner (3 marks of existence, 4 noble truths, 8-fold path, 9 virtues, 32 marks of the great man, 36 streams of desire, 40 objects of meditation…), in sutras and in surviving scriptures. Much of his teaching remains misunderstood in the West, particularly the idea of karma as a kind of ethical credit-debit system. Yet in a contradictory move, the Buddha uses his desire to conquer desire, something which would seem to be impossible. So long as a desire to conquer desire remains, then desire is there, but the vague concept of enlightenment is intended to overcome this. In a contradictory way, life and its sensuality is rejected in order to experience a more intense state of happiness and an end to physical suffering. The Dhammapada, again:

‘Leave the past behind; leave the future behind; leave the present behind. Thou art then ready to go to the other shore. Never more shalt thou return to a life that ends in death.’

The other shore… ‘The loss of desires conquers all sorrows.’ I used to feel this way, and used to blame my undeveloped and unreflected-on moods and motivations as great problems that needed conquering. Some of the strongest kicks come from self-cruelty. But it is desire which begins and enacts change in our lives of any kind, and fear which restricts or blocks it all together. And desire remains important, most important, in discovering ourselves and enacting the behaviours and plans that enable us to become most happy, self-sufficient, in short, free. Yes, no-one can conquer a person who has already conquered theirself. But that self-conquest comes in recognising and enacting what makes one happy. Here Spinoza is most insightful among all philosophers: it is in recognising our joy, understanding what and why we desire, and then bloody well going ahead and enjoying that joy, that desire, which leads to a supreme happiness. Only those moments of happiness do you feel yourself growing, maturing. I’ve had a series of potent doses of such happiness on this trip that I’m feeling like Alice in Wonderland, suddenly grown in stature, unable to fit back into the confines of my old way of thinking, my old dependence on work as social validation, my old little life with its little compromises, weekend treats, and scarce time for anything remotely dangerous.

There’s a cabinet for Percy Bysshe Shelley, born and raised in nearby Warnham, a childhood spent playing and exploring this area. His works make me think some more on these themes, with his passionate calls for a deepening of feeling, a belief in the possibility of change through the imagining of a utopia, a place of change enacted; and his belief in human self-sufficiency to overcome repressive forces that use superstition, exploit ignorance and institutional power and then deploy violence. One sees this in all his works. He recasts the story of Prometheus so that the tragic thief of fire overcomes Zeus and the tyranny of the gods. A wacky tale about ‘The Witch of Atlas’ has the sorceress creating a hermaphrodite out of fire and snow whilst foreseeing a utopia for all humankind. His ‘Masque of Anarchy’ attacks the army which killed fifteen and injured many more at Peterloo in Manchester in their campaign for democracy. There’s a facile belief in all these works of a pure state of being outside power, one that recurs and is most popular in the children of the upper and upper-middle classes, something we looked at in the ‘Bees of England’. Here, Shelley contrasts ‘Freedom’ against ‘Slavery’: any study of human history indicates there has never been anything conforming to the standards of the former ideal, nor any total submission to the latter, and much complicity between the two. But its argument for peaceful protest has been influential, particularly for Gandhi, who would quote Shelley and the Masque of Anarchy:

‘Rise, like lions after slumber

In unvanquishable number!

Shake your chains to earth like dew

Which in sleep had fallen on you:

Ye are many—they are few!’

Shelley’s claim is spurious, that moral guilt would shame intrinsically violent and defensive state institutions into backing down and supporting the will of the people (‘blood thus shed will speak // In hot blushes on their cheek’). Mass graves across the world do not corroborate this, nor does Peterloo. This appeal to the moral majority has had a depressingly conservative effect on political resistance, to the point that even today, disobedient citizens believe that simply calling themselves the 99% is sufficient for a legitimate transformation of government, or that arrests, surveillance or violence by the police is an outrage. Outrage against what? Political opposition is be a far more serious business than moral standards, never won by ‘passive resistance’, but through prolonged struggles that use effectively targeted violence alongside community activism and alternative political models.

I disagree with Shelley, but at times love his works, and love their effects in energising a desire for change in others. His descriptions of love, or what I’d call desire, are of a feeling inexhaustible, ‘eternal’ as he idealised it, a permanent possibility. ‘I think one is always in love with something or other: the error, and I confess it is not easy for spirits cased in flesh and blood to avoid it, consists in seeking in a mortal image the likeness of what is, perhaps, eternal.’

I drink coffee and write outside the town’s shopping mall afterwards. ‘That wobble on the Thames, it was good… people were energised by it’, say two businessmen to each other over lunch, beside me. I exit Horsham and cycle south-east, riding along major roads that bring me back over the South Downs. I cycle through the villages of Manning Heath, Cowpoke, and Bolney, then thread through towns familiar to anyone gazing at the station boards of London Bridge: Burgess Hill, Haywards Heath, Uckfield, places you always heard but could never guess. I imagined them as tiny hamlets, a triangular village green with a few moo-cows strayed upon it, a village pub with a tweed-only entrance policy. No no, they are instead snotty slithers of suburban housing that neither begin, centre, nor end. I cut off through villages of Wivenfield and Wivenfield Green, through undulating but uneventful countryside. I’d had hopes that there’d be some secret wilderness, just hidden o’er yonder from the Great Wen, but the South Downs is mostly agricultural countryside, and at times one is hardly aware of being in a national park.

Eventually I reach Lewes, a small and old market town cut deep into a valley and surrounded by white chalk cliffs. The road dips into the town, threading through 18th and 19th century housing, quickly concluding at a small town centre defined by a Waitrose and a long High Street that cuts the shape of the town. Use this as an axis. I take on one end first, passing old Fitzroy Hall and Waterstones bookshop, crossing a bridge and passing Harveys brewery, producer of distinctive and pleasurable south-east English beer. There are more antique stores on this edge of town than most settlements five times Lewes’ size would require, but the effect is twee, harmless distraction. Petworth made a similar trade in overpriced bric-a-brac. Young men and women sit on benches by the river, by the shops, gazing either wistfully or diplomatically at some shared encounter. I pass them and envy them the opportunity of learning love and its errors again.

Lewes is not the birthplace of Tom Paine, but it’s the town most associated with him. After my collection of his writing was destroyed by the rains of the Lake District, I make a point of picking up another edition of his works. Inside Waterstones, I take time to read through Owen Jones’ new diagnosis of the Establishment, similar in tone to the pamphlets of the Chartists, yet at root little more than a manifesto for his own activity with its calls for outriders to progressively lead a Labour Party or TUC that has found its way. It takes a diet-Marxist view of the establishment as one conspiratorial grouping tied to a common and uniform set of beliefs and practices, a view I’ve regrettably shared in the past, oversimplifying different interest groups into one, overinflating their cohesiveness and power. A conspiracy of the system! William Cobbett called it ‘the thing’ whilst on his Rural Rides. Sometimes there’s polemic value in systemic simplifications about the ‘haves’ and ‘have nots’, but there’s a mistaken value here in assuming that crudely oversimplifying and then attacking the bad deeds of a ‘rotten core’ will cause the many to wake up, smell the reason and create an eternal democracy. Things are grey, they always have been. Fear is more operative than hope on an individual and communal basis. Few have met or would openly obey this thing called establishment, as few would acknowledge and obey the fears, weighted traditions or habits engrained in their behaviours. But Owen Jones is a nice continuation of a long-standing tradition of libertarian pamphleteering and polemic, particularly in a town where Tom Paine first started causing trouble for the establishment.

I get talking to a couple of young women whilst browsing. One is from Lewes, the other Brighton, both are warm, friendly, and quick to advance to political possibilities. The Lewes girl is particularly fiery, ‘I just can’t leave here’, feels… ‘Trapped.’, as emphatically as the punctuation suggests. But every gesture expresses a power to overcome this with ease, and as I read, some embedded emotion or frustrated desire binds her to this odd little town. She’s had her own flat here since she was sixteen, but finds the place insufferably small. She’s worked in many of the pubs and advises which have drug or violence problems and which do not, but ultimately ‘there are three main families in the town. And if anything kicks off, they’ll get their people out. And if you don’t have anyone, there’s nothing you can do’. The crampedness and myopia is tangible, but this is a feature of other small towns and certainly of islands, as I tell her. What stands out about Lewes, I ask, enjoying the opportunity for playful antagonism. She smiles, though there’s frustration there. Half-jokingly, she says that Lewes is on a meridian line, an underground leyline or energy line of a kind. ‘So there’s something in the water?’ ‘Yes, don’t drink the Harveys!’

But she has a point: a surprisingly high amount of strange things have happened and do happen here. The town’s Bonfire Night celebrations are world-renowned for their lairiness. On the 5th November a saturnine cloud drifts over the town, as seven local bonfire societies make processions through its streets and then set fire effigies of Guy Fawkes, the Pope, Spongebob Squarepants, Theresa May, or whoever’s recently been in the news. Bangers are thrown, effigies exploded, fireworks fly hither and hither and it’s common for spectators to be injured in the festivities. Bonfire Night has special significance in Sussex. It’s curious that the event is now seen to be relatively family-friendly. Curious too that the image of Guy Fawkes as immortalised in Alan Moore’s ‘V for Vendetta’ is as a pro-democratic revolutionary, rather than as a plotter who wished to wipe out the country’s parliament and have an unpopular minority Catholic monarch head the country. The town takes the anti-Catholic origins of the festivities seriously. ‘Burn the Pope!’ is freely shouted.

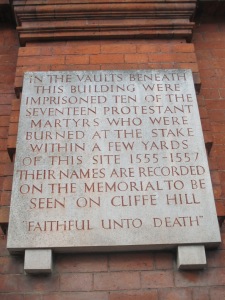

Disappointing but not unusual for the more insular and unfriendly civility of the south-east, ‘outsiders’ are openly discouraged from attending, though that doesn’t stop thousands from cramming in, buying hot dogs and dropping silvers into charity buckets. But serious locals will talk about Lewes’ reputation for harsh justice, of the public burning of a family of ‘witches’ and of seventeen open Protestants between 1555 and 57 during England’s momentary return to Catholic rule. Even some of the Easter 1916 rebels were imprisoned in the town later, including Eamon de Valera, later president of Eire. ‘The great appear great to us only because we are on our knees: let us rise’, words of James Connolly, a socialist before a nationalist but the two overlapping.

But it’s Tom Paine the town’s most associated with, another revolutionary who fought for republicanism and social justice through the pen and the printed press. He argued that all people were equal, and should therefore have the vote, that hereditary power was unfair and corrupt, that a progressive tax should be used to ease poverty, that a government should be constitutionally based on equal, fair and just principles. He was a jack of all trades and a master of none, travelling across England as a teacher, tobacconist, corset-maker and excise officer, his ventures and marriages quickly failing. He is nearly finished off by Typhoid fever on the passage to America: had he died, modern history would be quite different. His pamphlet Common Sense energises the struggling American independence movement; he later travels to France, where his Rights of Man persuasively argues for equality and human rights, and makes the case for the democratic French revolution to the rest of Europe. Paine always stuck to his ethical scruples, usually to his disadvantage: he loses favour in America after attempting to rat out a deceptive ambassador, whilst he nearly dies in prison in Revolutionary France for opposing in principle the execution of the king. He is tried in absence in England and sentenced to death for believing that human beings were equal, and should be governed as such; in his final years, Paine goes about alienating almost everyone, criticising organised religion, slavery, and landownership. Only six people attend his funeral, including two black freedmen who were his friends. In a final bizarre twist, his bones are bought by William Cobbett to be buried in England, but Cobbett dies before arranging this and the bones are spectacularly lost. Buried nowhere and everywhere, a man of the world, Tom Paine, an all-too human figure who ought to be a hero to our age.

“What are the present governments of Europe, but a scene of iniquity and oppression? What is that of England? Do not its own inhabitants say, it is a market where every man has his price, and where corruption is common traffic, at the expense of a deluded people?”

I wander around the town, finding first a statue of Tom Paine outside the town’s modern library. I wander past a Turkish Bath and up the old high street, past trendy pizza chains and twee cafés. I stop for a drink in the White Hart Hotel, where Paine would address fellow-members of the ‘Headstrong Club’ in the early 1770s. I talk to the barman whilst supping on the local Harveys, bland but homely, and he tells me about the ghosts in the pub, about spectres wandering through the fireplace, or guests’ reports of hot feet in room sixteen where the burnt martyrs stayed four and a half centuries ago, and of strange noises in the bricked-up tunnel that once linked the pub to the town castle. We laugh. He’s part of his village bonfire society, and tells me how the town goes ‘just mad’ at bonfire night. His society meet across the year, collecting money and working on their guy. They opt for the more family-friendly: instead of Saddam Hussein or Colonel Gaddafi, Shrek, Spiderman or Spongebob Squarepants. ‘If you walk around, so little has changed, you can imagine yourself being here a hundred years ago and seeing the same buildings,’ he muses. He sees the society as part of his deep connection with history, with his history, time zones overlapping through shared experiences and customs.

I head out, past a pub called the ‘Rights of Man’ which on any other day I’d happily end up in, then drift up towards the town’s small castle. Lewes is a wonderful place to explore. Nearby is the tumble-down Black Bull Inn where Paine lived with his wife and sold tobacco, and opposite stands the Thomas Paine Printing Press. There are some beguiling wee alleys off the road, like Rotten Row, and a series of enchanting old bookshops, pubs and houses. One could spend a long time here, perhaps too long. The light’s setting and I cycle out.

The road south towards Brighton are full of traffic, and the ride is relatively flat and uneventful. I come off at Falmer, a small settlement on the north-eastern outskirts of Brighton where the main buildings of the Universities of Sussex and Brighton are based. I’m here to visit the University of Sussex, a modern sixties-build spawned during the expansion of higher education. There were a series of student demonstrations here last year, ‘Occupy Sussex’, protesting against the privatisation of parts of the university’s facilities and low pay for academic staff. They occupied Bramber House for five days, where the Student Union and a conference centre is based. The occupation was marked by the resilience of student occupiers, and the harshness of the university’s response, who used police and eventually a court order to evict protesters, and permanently suspending five. I wander inside, and pick up supplies in a Co-op supermarket where students sleepwalk-shuffle through the aisles, entranced by their phones.

I check with one student that this was the building where the occupation happened, wondering about how students here remember it. Her name is Becky, and she’s a business student here. ‘This is the place. I remember, it was last year. There were bouncers around’. I ask what the legacy was. She’s unsure, but she speaks with anger about the university’s draconian attack on protesters exercising their right to protest, and ties it to the vice-chancellor’s plans to increase student numbers by 25% without building any new facilities or recruiting new staff. Anything jeopardising this mass recruitment would be harshly punished. ‘Lean production’, methinks.

She doesn’t feel political, but in discussing her studies she presents what she avows is not a feminist position but certainly is in its arguments for equality in a sexist culture. She tells me that there’s sexism in business, but that she doesn’t want neither positive nor negative discrimination (‘ah you’re a gentle lady, come this way’, she jokes), but wants to be treated and recognised as equal. She describes feminism as a kind of man-hating, ‘til I suggest that her views conform entirely with the early feminist programme for equality, in votes, in work, in personal lives. Her talk is fiery and political, but there’s a discomfort, scepticism, a refusal to give anything a term, to give talk about things in the debased currency, political.

I ride into Brighton along a busy main road with a bike lane, and enter a small city with a marked prevalence of social housing. I hear that a third of the city is receiving housing benefit, but this doesn’t automatically suggest poverty, unemployment or a culture of worklessness, more an issue with high rents. Brighton is hip, and has been for some time, popular with Londoners since the dirty weekends of the early 20th century. Property prices have been driven up. Wouldn’t a new house-building programme alongside rent caps empower tenants whilst stopping the state from subsiding the greed of landlords?

I ride on, past takeaways, pubs, a cheery if seedy tattiness presiding. The town’s successfully managed to hold back the more irresponsible instincts of developers and speculators, and there’s only one idiotic retail park I pass, not three or four as is usually the case with a town this size. In fact aside from the modern University of Brighton buildings close to the seafront, there are very few new buildings whatsoever. Much of its centre retains the narrow lanes, promenades, crescents and stuccoed terraces of the Regency period of the late 18th century, with Brighton booming as a fashionable spa resort over the 19th century. There are countless pubs, bars, boutiques and cultural centres here. I drift around, past the Royal Pavilion with its fanciful minarets and onion domes, and a garden where Bob Dylan’s ‘Blowing in the Wind’ is sung to an audience of drunk vagrants. I pass the Grand Hotel where Debussy writes La Mer, and along the seafront where mods and rockers would gather every bank holiday on their scooters and bikes for a mass beach brawl. Those were the days, crime-free, unplagued by violent teenage gangs, right… Brighton’s sole surviving pier, the Palace, dizzily flashes with gaudy lights and cheap spectacles, the burnt remains of the West Pier not far along the coast.

I’m staying with friends tonight, Erin and Neil, who live up steep Albion Hill just behind the main town centre. I push past a couple of sixties’ estates til I reach the Albion Inn, which is for sale, indicatively. Erin and Neil both work in film. Erin’s just received a scholarship to start a funded MA at Cambridge, and will be moving in a week. She’s excited, and all of us are quite curious about what studying and living will be like in such an ‘elite’ institution, particularly living in one of its ‘colleges’, which seems to be compulsory. She’s excited but already hampered by an innumberable number of ridiculous extra costs, like £90 a term to pay for cafeteria without any use, £10 for extra bedding whenever one wants a guest to stay, £1000 to have a shared kitchen above the cost of the rent, and so on. They must compulsorily attend the ultra-formal ‘High Table’ dinners where everyone dresses in gowns on long tables and hear speeches about how excellent and top-class they are.

It reminds me of the champagne cork theory: is there ‘social mobility’ in allowing someone like us, without an expensive private education with added tuition, without a wealthy family, into the elite corridors of Oxbridge? She’ll be finding out, but she’s nervous, though having just come out of a secretarial career working under some pretty loathsome property developers, her resilience is high! Neil is a film writer. Their small flat is just filled with DVDs. After a hedonistic period in his 20s, he’s established himself as a successful editor and writer. He shows me a case of DVDs received as payment by a broke film company for writing an essay about Richard E. Grant. ‘After raving about Australian films for years’, he’s just been appointed to curate a highfalutin film festival. We talk about Brighton and about tax, the need to harangue HMRC for a rebate, that millions of pounds in tax goes unclaimed. Erin tells us how in Australia, each citizen was given $600 each from a large reserve of uncollected tax rebates. Were such a thing to happen here!

We head to Planet India, a local curry institution which deserves full marks for its menu descriptions alone (‘Doesn’t sound that great, just trust me, a quintessentially Gujarati dish’). The dall is delicious. We drink beer and talk. Erin’s just come back from Japan, and shows us some pretty fruity magazines found openly on sale there. For all the meekness and repression of extroverted social mores, expected particularly of women, there’s a bizarre and open hentai sexualisation of young women everywhere. Tattoos are frowned on, drug use receives severe prison sentences, and no phone-calls are permitted on trains. The salary-man is exulted as a masculine cultural hero of the workplace, and she describes a crippling conformity at work compared to our standards. But are we not strange in turn, another island nation, gripped by an unspoken but all-too-real hierarchy of social class, from the zero-hours migrants sweeping the streets to Queen and her corgis behind palace gates? Only the poorest seem to pay taxes, and property rules the waves, even if no-one seems to own up to owning anything.

We head back to theirs for some more beer and conversation, with the X-Files in the background. Whilst they bemoan endless film spinoffs and remakes, a commercial reluctance to experiment with visions of the future, my hand examines the worsening state of my leg. A long, fascinating, tiring day. Only four more to go.

I hope that your knee is coping OK and you and the bike manage to complete the last stretch into London.