‘I was in a world of my own.’ – young man outside Tesco, Piccadilly Gardens.

The morning light slithers under the curtains and into my eyelids, rousing me from a good night’s rest on the most comfortable of beds. I’m being hosted by Jacqui in Trafford in the south of Manchester. We drink coffee and make plans for the day.

The previous night we’d plotted some places to explore together, Jacqui having the day of work and looking forward to venturing across a city she’s still not entirely familiar with. After stopping by her workplace, Siemens, a lego-brick creation on Princess Avenue, we jump on Manchester’s tram system and head towards Salford Quays.

Riding through Manchester, one quickly senses that this is a city expanding and growing in confidence. The tram has recently been extended out to various satellite towns, connecting up the area like the spokes of a wheel to Manchester’s central hub. More stations are being built and infrastructure is being invested in, something that this city alone can boast of, outside London. The trams are modern, speedy and regular, and we quickly arrive at the planner’s utopia of Salford Quays.

There’s little sign that this was once a working, smelling, sooty centre of docking and shipping. Aside from the inlets of the waterways, no crane or warehouse remains of the large Manchester Docks that were once Britain’s third busiest port. They closed by 1982, the ship canal being too cramped for containers. The area fell into disuse until the late 1980s, when Salford council bought the land and secured enough funding and investment to transform it into Salford Quays, a dockside resort of high-rise luxury apartments, offices and a large mall named after the painter F.S. Lowry.

‘I would stand for hours on one spot … And scores of little kids who hadn’t had a wash for weeks would come and stand round me.’

The docks that Lowry knew are long-gone, though the poverty of Salford isn’t too far behind all this showiness. We disembark and walk towards the main cluster of offices, some starting to show up a rusty and grubby neglect, others still confident in their angular shapes, piercing the heavy grey clouds that mirror the tones of the pavement. There are a few people milling around, mostly office workers by the looks of it, though a large gaggle of Canadian geese block our path a while.

In the distance is Old Trafford, home of Manchester United, the city’s major footballing export. It is the third-richest club in the world, and one of the few clubs to truly thrive in the transformed world of football, where players receive six figure weekly wages, clubs float in the stock market, and teams advertise all manner of consumer products.

Salford has made a big deal of the ‘innovation, leadership and partnership’ that structures like these on the quays intend to provide. On the ground, one is looking up at castle-like offices, defensively built in coloured glass in some Archimedean strategy to deflect public scrutiny. Confident dreams have been set out in the council’s ‘2025 Salford: A Modern Global City’. At the heart of this vision is an overreliance and presumption that economic growth can be continually maintained through retail, public media, immaterial labour and property speculation. It seems a little dubious, though the relative newness of the builds here imparts a confidence.

A new MediaCityUK building stands close to an ITV structure, both a combination of large glass-plates and bendy shapes of a kind picked out of an architect’s catalogue, feasible from Delhi to Derby. There’s an eerily deserted public square, an open space with benches but depopulated. One feels watched passing through, a combination of the high-rises and the winds perhaps, but look hard and cameras are trained down. There’s a large screen in the centre with some rolling news on, another testimony to a supposition that human rights would be infringed where there’s no access to distractions.

Salford’s supposed to be the case in point for riverside regeneration. Some credit is due: the waters were once heavily polluted here, and the derelict warehouses and docks would’ve been ugly and depressing eyesores, difficult to maintain and impossible to preserve in their current form, their function obsolete by the huge containers required by rampant international trade. But the past has been too crudely obliterated here. Nothing remains, not even a token crane or one case-in-point refurbished warehouse. Not even a chimney. Instead stand proudly the high-stakes high-investment high-rises of the future according to the year 2001. They will date quickly, as some already are; and will age badly. One will need to revisit Salford Quays in twenty years to understand its ‘regeneration’. The people and their stories remain absent.

Indeed, Salford feels like an unresolved problem in the splendour of Manchester. The over-investment by the quays seems like a belated and inappropriate attempt at a gift by a neighbouring city that’s creamed the profits, industry and fame of its hard-working, hard-suffering neighbour. It’s like the adulterous lover’s gift of flowers. Why do we speak of greater Manchester and not greater Salford, or at least, the cities of Manchester and Salford, or the Irwell Valley?

I’ll visit the backstreets of Salford a couple of days later, and will discover an extremely run-down series of streets and communities little more than a stone’s throw from here. Salford remains a destitute place in parts. But it doesn’t seek pity. There’s a gritty pride in these places too. Writers from this area have captured it in works that now seem to speak for the north as a whole. Don’t forget the roots of Shelagh Delaney, born in nearby Broughton, whose 1958 play A Taste of Honey captured Salford in all its fissures and contradictions, be it class, gender, race or sexuality, undermining the clichés of a docile, conservative, flatcap-doffing northerner.

‘We used to object to plays where the factory workers came cap in hand and call the boss ‘sir’. Usually North Country people are shown as gormless, whereas in actual fact, they are very alive and cynical.’

Or consider Walter Greenwood, whose 1933 Love on the Dole captures working-class life in Salford during the unemployment-blighted Thirties. It’s an angered, overcrowded and imprisoning landscape, a ‘jungles of tiny houses cramped and huddled together’, where ‘men and women are born, live, love and die and pay preposterous rents for the privilege of calling the grimy houses ‘home’’. It’s a landscape of high chimneys, squalid overcrowding and teetering slums. The abject poverty has been lessened but remains there, albeit hidden from here. Unemployment’s become masked by ‘self-employment’ or being forced off the dole altogether, whilst a decades-long attack on public ownership, workers’ rights and the social right to welfare is recreating the conditions described by Greenwood, ‘the tragedy of a lost generation who are denied consummation, in decency, of the natural hopes and desires of youth.’

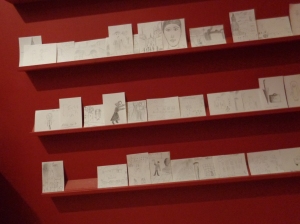

Time zones overlap. We head into the Lowry centre, where a fine collection of Lowry’s sketches and paintings can be seen with free entry. Like Greenwood, Lowry chronicles the tall chimneys that once haunted these scenes, and the crowds whose movements are at times aimless and sad, and at others possessed by a dynamic, unconscious energy. ‘They are ghostly figures … They are symbols of my mood, they are myself.’ As well as his more well-known factory scenes, the exhibitions show that Lowry’s also a very gifted writer, with a cold and melancholic poetic flourish. He drew and painted as if it were some cursed superpower, some means of exorcising the ghosts that remained of people’s miserable lives. ‘Had I not been lonely, none of my work would have happened. I should’ve not have done what I’ve done, or seen the way I saw things.’

Jacqui and I leave the postmillennial amnesia of Salford Quays and tram it back into the centre. We disembark at St. Peter’s Square in the centre. The place is a building site. Nearby is the Manchester Free Trade Hall, now a Radisson hotel, a cipher of Manchester’s deference to the flow of money, its obsequiousness to ill-thought out and aggressive property developments. The Sex Pistols once played here, apparently jolting into life the Buzzcocks, Joy Division, the Fall, and Morrissey, if the Manc music chroniclers are to be believed.

There’s a tiny plaque here to the Peterloo massacre, where a crowd of around 60-80 000 protesters demanding parliamentary reform on 16 August 1819 were charged by the King’s cavalry. Fifteen were killed, and hundreds badly injured. These people demanded the right to vote and for proper, fair representation by members of parliament. They demanded an end to the hunger, malnutrition and unemployment that wracked their lives. After the dust settled, little changed. It took successive protests, riots, and the fear of working class power to enact even the most basic political change.

We wander round to Albert Square, quiet and frequented with lunching office workers in the afternoon. Here’s a great place to look up, as one always must to appreciate any city. We take in the Town Hall in its neo-gothic splendour, its statuettes of knights and kings and queens. A rainbow flag flies from its roof, a symbol of gay pride, wonderful and totally unthinkable even two decades ago, a sign of progressive social change and against the grain. In 1987, the British Social Attitudes Survey found that 75% of people polled thought homosexual activity was ‘always or mostly wrong’. Some twenty seven years later this has surely reversed.

Public opinion is never a fact, nor should it be the one foundation of democracies. The success of Pride and the hard-won struggles for equal rights should be considered as kin of the right to vote: hard-fought victories against an oppositional authoritarian establishment, one powerful enough to dominate bodies and minds. Victories for equality, liberty, toleration and freedom have happened. Our bittersweet moment of cynicism and doubt is just another stage-set that could be dismantled.

Adjacent is a more recent extension, Art Deco in style, a city growing in confidence. Close by in alabaster white is the Central Library with its classic pretensions, columns and arches, a nascent belief that Manchester’s citizens would thrive through access to learning and culture, a notion unfortunately considered too paternalistic today. WiFi and free computers to browse Facebook are a safter bet. Then there’s the red-brick Midland Hotel, fussy and self-important, next to Bridgwater Hall, its brassy glass façade of the modern age. These styles are ill-fitting, weird yet in a city defined by its juxtapositions, feasible, even characteristic of it. They are the expressions of money filtered through different cultural presumptions: civic pride, crafts, a return to classic values, the adoration of property and free markets, each side by side.

Hunger’s creeping, so we head through the Northern Quarter, a section of the centre popular with students and known for its trendy bars. Down the most grubby of backstreets, amusingly named ‘Soap Street’, I’m taken into a hidden canteen called This & That, serving very cheap Indian cuisine in a cramped room that seems only recently converted from a taxi business or disreputable accountant’s office. Over formica tables we scoff vegetable curry and three veg, delicious and filling stuff. The place is packed with local office workers, students, street-cleaners, all in the know on this superb secret. ‘With Manchester, the more grubbier it is, the better the food’. It’s a seemingly dangerous rule for finding food outlets, but one worth testing!

We drift out against the mid-afternoon swells of office workers, students and wandering persons. Each has their head down, headphones in ears, checking their emails, lost in their digital personas. We struggle to navigate through these waves of the blind, and the experience is frustrating for us both. People fail to look where they’re going, bumping into us and others, not apologising. Moving around Manchester on foot is not dissimilar to London. For clichéd notions of Northern civic friendliness, head to the other side of the Peak District!

It brings to mind the words of Lowry we saw earlier, which now seem to make sense amongst the crippled social interactions of strangers here. ‘I was sorry for them, and at the same time realising that there was really no need to be sorry for them because they were quite in a world of their own’.

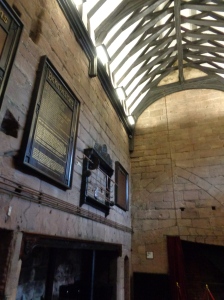

Besides Manchester’s small cathedral is Chetham’s library. Founded in 1653, it’s the oldest public library in the English-speaking world. Its interior suggests that neither its stock nor its structure have been renovated much since that time either. The building complex itself is of the 15th century and is immensely curious, full of strange chambers with hunting memorabilia, portraits of distant luminaries centuries old, and the most delightful and homely smell of musty papers and beeswax polish. Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels used to meet and work in this library, and one can still see the desk and the alcove where they sat together and studied during the 1840s.

Engels later produced a sociological study of the workers of Manchester and Salford, The Condition of the Working Class in England. Passages from it seem meaningful in the current moment:

‘The town itself is peculiarly built, so that a person may live in it for years, and go in and out daily without coming into contact with a working-people’s quarter or even with workers, that is, so long as he confides himself to his business or to pleasure walks. This arises chiefly from the fact, that by unconscious tacit agreement, as well as with out-spoken conscious determination, the working-people’s quarters are sharply separated from the sections of the city reserved for the middle-class; or, if this does not succeed, they are concealed with the cloak of charity.’

I later cycle out to some of the impoverished, hidden-back suburbs of Manchester and discover this. Places like Moss Side, Hulme, Salford and Cheetham. The suburbs with their low rents and bad transport connections are becoming concentrations of the poor, as gentrification of inner city suburbs reverses the 20th century pattern of social class and neighbourhood spaces.

There’s a small exhibition of works in the library, but the place suffers from a dearth of information signs or booklets that explain its history to the passing visitor. I read from the diary of Ernest Leech, a British soldier fighting in the First World War. On 10 October 1917 he shares these moving words of being lost, disorientated, which seem to capture my mood drifting through Manchester streets.

He was

‘quite lost but sure of direction from stars; very few men understand stars. Our men in shell holes and very cold, not watching. Lights on all sides of us. At day break went back to Calgary.’

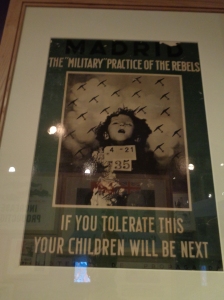

Cheetham’s is well worth the visit, and pleased with the discovery, we move onto the People’s History Museum to find out a little more about Manchester’s other social histories. It’s situated in a modern building and refreshingly retains the contemporary political commitments that the struggles it exhibits demanded. It’s also fun, interactive yet remains informative. There are some superb exhibits about the Peterloo massacre, the growth of Chartism, and the growth of trade unions, which were initially illegal (remember our slave abolitionist William Wilberforce in Hull? He supported the Combination Act which censured them). There’s some surprises here too. The museum records the government’s strong opposition to the establishment of old age pensions, maternity benefits, and women’s suffrage, reinforcing the lesson that the government of the day will generally attack, block and repress any kind of movement that seeks to empower the peoples of this island. They will not budge, unless they are made to.

So many lessons, so many histories. We part ways. I am off to give a pint of blood to the NHS and to a study measuring variations in intervals between blood donations. It’s always been a quick, easy and painless process, and the nurses tell me about Jamaica, about Manchester, and about the surprisingly common practice of photos and selfies with a wire in one’s arm.

Rain’s falling hard. A bus takes me back to Jacqui’s, via Manchester’s district of universities, and the residential sprawls of Whalley Range and Hulme. We have a relaxing evening after all that walking. ‘You are enough’ is written over Jacqui’s kitchen door, an important and easily-forgettable reminder to ourselves not to feel overwhelmed by the stresses and anxieties that come like consequences of an unfortunate modern age. ‘Love – Live – Laugh’, that’s enough. We watch some films, eat noodles and drink tea til the clock pronounces time to sleep.

The next morning we part ways for good. Once again, in Jacqui I’ve met another stranger who has become a good friend on this journey. Near her’s is leafy suburban Stretford. I head down King’s Road, where at number 384 a young Morrissey once lived with his family. Johnny Marr turned up announced here in May 1982. The pair discussed music, discovered shared influences that they lived for, and after a few tentative song-writing sessions, the Smiths were born. There ought to be a gladioli stall outside the house, or at least a heritage blue plaque, but then Morrissey remains today a self-appointed enemy of the music and political establishment. The one tribute I find is a cycle lane all along King’s Road, cutting through some surprisingly dull, all-too-pleasant suburbia, a place to dream out of, and escape.

I am cycling south, through Witthington, Northenden, suburbia snaking round over itself, becoming more leafy and samey, a landscape built during the 1920s. I pass through Sharston and arrive by Wythenshawe, in an area of council semi-detached semis that could be anywhere in England. Again, Manchester bares its teeth, and incongruously dizzying juxtapositions stand cheek by jowl: the pebbledash Seventies monstrosity of the Britannia Hotel next to a fine Art Deco building which is now a Jehovah’s Witness hall. I arrive in a small residential area besides Manchester’s airport, planes landing a few hundred metres overhead. I’m staying here with Amy and Saad, friends of mine. I say hi, drop my bags out, and cycle the ten or so miles back into the centre, hungry for another hit of this strange and not particularly affable city.

The road cuts along suburbia, then passes through Rusholme, named by the council as ‘Curry Mile’ and populated with eateries than span the countries of Asia. It’s heady with buses, particularly as Rusholme passes Fallowfield and the universities, and hits the centre. Edinburgh Cycle Cooperative is along this stretch, and I pop in, hoping for a quick tip for fixing my malshifting gears. A young feller fixes it for free, and tells me about their cooperative model. They have around 260 staff who each have an equal share in the business, and equaly share a bonus. They meet and share their voices about how to run the business. Each person’s opinion is valued, and collectively the wisest and best-informed decisions are made, as each person has an equal and shared stake in what happens. Cooperatives strike me again and again as the best way to administer any business or organisation. They strive towards mutual benefit, which brings together diverging interests and backgrounds into a single focus. Well-administered, they dissipate resentment and conflicts and ensure that, to the best its members can foresee, every possibility or idea is aired and considered. Running anything for private profit by contrast accelerates a parasitical greed, disempowers and demotivates workers, and leads to a topsy-turvy domination of a few managers, often misinformed yet anxious to defend their privileges, over a large body of workers routinely ignored.

Manchester’s instructive again here: the first successful co-operative was founded in nearby Rochdale. The Rochdale Society of Equitable Pioneers was established in 1844 by local weavers and artisans to sell produce they otherwise couldn’t afford. The model worked, and hundreds of cooperatives were established across the country. Coops in Yorkshire and Lancashire joined together, forming what would become the Cooperative Wholesale Society, initially based in Manchester. That supermarket and bank remains today, in heavily bastardised and compromised form.

But from this first Society came the Rochdale Principles, the basic elements of a successful cooperative, like open and voluntary membership, democratic control, promotion of education, and the distribution of surplus in proportion to trade. Pubs, housing, even football clubs can be run along such lines, like F.C. United of Manchester, a community-owned, democratically-run club formed by Man United fans in 2005 after the Glazer family bought the club in dubious circumstances.

I leave the bike shop and reach the centre, passing the Holy Name Church and Manchester University, where W.G. Sebald and Alan Turing each worked at various times. After a little difficulty, I locate the Hacienda, Manchester’s famous if under-populated Eighties nightclub owned by the city’s Factory Records. ‘What a fuck up we made of it’, remembers Joy Division and New Order bassist Peter Hook, nostalgically. It is now turned over to luxury housing, an end similar to that of the Free Trade Hall. Money rules the roost. I pass back through Albert Square. I’ve been blessed with the helpful and friendly advice of John Fitzgerald, who has emailed me all manner of tips and advice about Manchester. He has pointed me to the unique mixture of building styles, all higgledy-piggledy in this city.

‘It’s not a ‘pretty’ city by any means but I don’t think there’s anywhere else in the country which does this juxtaposition of old and new quite so well.’

It’s on his recommendation that I sneak up to the car-park by Shudehill, between the Northern Quarter and Victoria Station. At the top floor one can view the entire city. Ignore the Samaritans’ signs, and to the south are flat, relatively empty expanses, and the north, a strange mish-mash of developments, office blocks and hotel high-rises littered here and there.

Terrace NQ is as pretentious as it might sound, but it’s an open bar in the Northern Quarter that’s happy to serve me both an espresso and a craft beer whilst I string together a series of impressions. I am a member of Manchester Left Writers, a new group of writers and researchers, and have been invited to join them this evening as their writer in residence. I sup on my oversweetened American IPA, a reminder of today’s drinking fashion for sweet drinks, be they alcoholic ginger beers, fruit ciders, or tequila or bourbon flavoured beers, each overly sugary. They are alcopops for people too pretentious to admit it. Even the American IPA of super-sweet Brewdog beers are far too saccharine for my tastes, and taste nothing like the older IPAs or bitters that graced the ale pumps of dirty dives a decade back. Still! An hour later I have my words – you can read them on my other blog here – and meet with Steve and David, two of its ringleaders, by the Northern Tea Power café.

They’re of a similar age and outlook to me – youngish men working in the cracks between university research and teaching, unsure of the future, struggling on a small income yet feeling barred from the traditional working class identity and pride that would come with such an income or struggle. They’re also big fans of The Fall too, so that’s also a good thing! They show me some of their recent publications. They’e just produced a superb series of postcards with messages like ‘Irony must cease’ and ‘Houses are for living in’, as well as a series of broadsides on the cultural and academic establishment, fine and fiery works.

They bring me upstairs to a backroom in a quiet boozer called the Castle. There’s a group of around ten here, suitably conspiratorial, a mixture of backgrounds, each committed to new left-wing writing and thinking. I read my words, then we talk about Manchester some more, the contradictions built into its landscape and stories. Is Manchester’s economic freedom compatible with regional political freedom? How can high-speed railways or new housing be marshalled or understood by a campaign for a political alternative that values collective ownership and the common good? We discuss these problems for hours over many a pint, mostly angry, but also unsure. We know what we’re fighting against, but what are we fighting for? – is a truism of many political groups, but with this group of people I sense that something interesting’s happening. They’re shortcutting through the bureaucratic fandangos and finger-pointing that have blighted other groups I’ve met with or participated in. Something’s happening here. Follow it, and participate in it too if you’re local – http://manchesterleftwriters.wordpress.com and @MancLeftWriters.

After drifting round Piccadilly Gardens on my own, I cycle back to Wythenshawe in an inebriated state. It’s dark and rainy. I manage to misjudge joining a bicycle lane near Fallowfield, and fail to spot that it’s actually raised, merely painted onto a pavement. I fly off the bike and onto the kerb and manage to tear my jacket and jeans, though I am improbably unharmed. I hope there’s CCTV footage of it, because it must’ve looked hilarious! I make it back to Wythenshawe in just about one piece, sneak into the back of Amy’s and Saad’s, and catch some zeds.

The morning’s bright. Rain’s promised again, but after days and days of it, it’s become the norm. A dry spell is to be cherished. Today I’m exploring further afield, and I cycle south, past the airport and out of Greater Manchester. I cycle through Styal, a village with many a gated home, then along a country lane past cows and grassy fields that eventually brings me into Cheshire and Macclesfield, a small former silk town. Like with the remainder of Lancashire, the mills are now dormant and most have been demolished, though some remain like Paradise Mills, and another has been repurposed into a heritage centre. It’s a small town that still retains the low and cramped terraces of its mill workers. The Hovis mill is in the distance, and we’re surrounded by rolling fields of countryside, a strange contrast to the compact overdevelopment of the town. People wander around slowly and with a degree of lethargic boredom through the town’s small shopping precinct.

In the visitor centre I find out about the town’s silk-producing history, as well as its more recent popularity with fans of Joy Division (like myself). There are cups, tote bags, postcards and even a walk-booklet one can pay for to follow the steps of singer Ian Curtis, who was brought up, lived, worked and died in this small town twenty or so miles south of Manchester. I find Armitt Street and the very small labour exchange where Ian Curtis helped disabled people find work, and on a parallel road I find 77 Barton Street, the house he bought with his wife and child, where much of his haunting, melancholic and otherworldly lyrics were thought out and written. It’s a surprisingly unprepossessing house that sits on a corner-bend in the road, with no monument or sign to its cultural importance. In the distance, those same cramped and pinched terraces, and further afield, a great mill that would’ve once smoked and hummed in a country plain.

I talk to local people as I wander round, who add details about the silk history of the town and tell me of its quiet, pleasant character. Umbro once made most of the nation’s football kits here, and Zeneca still employs. It’s not quite the ‘ghost town’ I was expecting after what I’d been told in Grimsby. I find the crematorium where a memorial stone to Ian Curtis stands, a groundsman helpfully leading me there. He finds it ‘weird’ that the stone has become a shrine to Joy Division fans. They get visitors from Japan, Australia, and all over Europe. By the grave are Alyssia and Arens, two visitors from Sicily and Parma respectively in Italy. They have a guidebook of Manchester’s musical history, and have come out especially to see the shrine.

‘Love will tear us apart’, such strange, evocative and possessing words. There are plectrums, coins, flowers and photo tributes here, and I leave behind a small electric candle picked up in Gretna. A friend at my old university, Jennifer Otter, has written an academic study of the ways and motivations of fans who commemorate Ian Curtis in this way, these modern pilgrimages to deceased saints, as young people attempt to navigate personal identity and community in a secular consumer society. Called Joy Devotion, it’s another curious fan product inspired by this remarkable singer and lyricist.

I leave the cemetery, passing the school where Ian Curtis and Joy Division drummer Stephen Morris went, and head back towards Manchester. It’s a long ride, and I pedal fast, as I have another appointment with the non-secular world.

I’ve arranged to visit the Didsbury Mosque and Islamic Centre in order to find out more about the Islamic community in Manchester, and spend a little time actually visiting a mosque. The mosque is in an old converted church in West Didsbury, a leafy suburb in south Manchester. Despite several expansions, its members have been keen to preserve its original heritage and character. I talk to Seth for some time, the secretary of the mosque. It was set up in 1967 by Muslims who needed a new space for their increasing congregation to worship. He sees no problem with the original Christian function. ‘Everyone’s allowed in. … We both worship the same almighty god, there’s no priority, Christian or Muslim.’

He’s been worshipping here since 1973. Through the fundraising and anonymous donations of its members it has expanded immensely, and I’m shown around several prayer rooms, alongside a new extension which will allow for more. Muslims must make five prayers per day, though the most important day for prayer is a Friday, the ‘Jumu’ah’ prayer, the day of assembly in Islam. He tells me about the five pillars of Islam, and about the ‘zakat’, he prescription that all Muslims must give 2.5% of their income to the deserving poor. I can’t help asking if the mosque has suffered any racist attacks. Seth emphasises that the place is non-judgmental, and that ‘that’s between them and their god’. He’s a wise, forgiving, kind and patient man, who listens very carefully, patiently asks my questions. He fetches me delicious mango juice before I leave, and after telling him about my journey, he offers his own counsel: next time, get a motorbike!

I leave Didsbury and re-enter the centre via Moss Side and Hulme. It’s ‘High Street’ is a huge retail park next to a brewery, a depressing yet I suppose honest reflection on household consumption today. I pass an advert for the charity CALM, or the Campaign Against Living Miserably. It’s a campaign to reduce suicides among men, through a campaign that encourages men to speak and talk when going through a hard time, providing a helpline to do this, and campaigning to increase recognition of the problem of male suicide in this country – suicide is the biggest cause of death for men aged 20-49 in England and Wales. It began in Manchester and was supported by Tony Wilson, and still draws in support from musicians, campaigners, affected friends and family members and young men themselves. It’s well worth supporting.

In Salford, I pass a bloody awful retail park and dip over into a maze of terraced streets around Coronation Street. They’re red brick but in a bad way, and I pass groups of bored kids with grubby faces playing about with rubbish left in the street. I find the Salford Lads Club, another mecca for Smiths fans, which is sadly closed today. The building’s in a little disrepair but is still well in use, bringing activities to local kids in this impoverished area. I take a couple of photos, until I notice a pear roll against my bike wheel. Some local lads are using me as target practice, pulling unripe pears from someone’s garden and flinging them at this stranger. Oh the misery of being a Smiths fan!

I’m not bothered, and encourage them to try harder. The weird bravado wins them over, and they stroll up to me and ask if the pears can be eaten. They’re hard to the touch, ‘too hard’, I say, ‘they’ve got to be soft’. One asks me if I’m a postman. The three each display learning difficulties, and the scene feels coldly grim. They go to the lads club, but have little else to say. They go back to throwing pears at me. I stand still and laugh, and they continue to miss. I manage to get a photo, and decide to head off, depressed and revolted by the area.

My final day of musical explorations ends up in Prestwich. I head via the centre, close to Canal Street, once Manchester’s main gay area and popularised in the radical Nineties TV drama Queer As Folk. Jacqui told me that today it’s ‘full of straight people’, meant without offence to me, but displaying the frustrations with some of the excessive commercialisation of the ‘pink pound’. I head north up Bury New Road, passing car forecourts and Indian takeaways that eventually becomes a large orthodox Jewish community by Prestwich. There are leafy parks, nearby hospitals, and a parade of shops and pubs, a little down-at-heel but settled, peaceful.

I pop into the Forresters, one of Mark E. Smith’s regular pubs I suspect. The long-time lead-singer of The Fall has lived in this area for decades. The Spice Girls play in the distance, but the heavily-beiged carpets, seating and walls of the pub reflect the sullen expressions of its mostly male, middle-aged punters, the majority sitting in silence, supervising the water-line of a pint of Holts’ mild. ‘He’s getting a bit of stick in the white horse so he’s gotta come down here.’ The windows are misted, and a sign says ‘no children, no exceptions’. It’s a good place to avoid a wife or disappear into one’s thoughts. ‘He’s getting good at it’, the locals joke with the barmaid about one man avoiding his spouse.

So then, Manchester. I’m not sure I quite like the city: it’s certainly more like London than it thinks, and it thinks a little too much of itself. Self-regarding yet intriguing, wracked with contradictions, missing today a voice in music, literature, arts or culture that can express these. Lost in a world of its own. I head back through the centre, along what now feels like a homely route, down Oxford Road, Palatine Road, out to Sharston and then Wythenshawe. I have dinner with Amy and Saad, pizza and Eton Mess, and we share our impressions. This is their city, their home, but they’re also thinking about the future, about a new life, about the difficulties of money, and dreams of working elsewhere. Uncertainty’s in the air. Manchester, so much to answer for.